Introduction

Across the globe, policymakers are raising the regulatory bar for investment products with ESG characteristics through heightened disclosure requirements and new naming and labelling rules. A key aim of such rules is to protect investors through enhanced disclosure while preventing intentional or unintentional greenwashing. The European Union (EU) continues to lead regulatory initiatives on sustainable finance, but other regulators, including the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), and the FSA of Japan (JFSA) released proposals for sustainable investment disclosure and product naming rules in 2022.

In this first of a three-part series, the ISS ESG Regulatory Solutions team leverages its Regulatory Sustainable Investment Solution to show what practical implementation of the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), as well as the fund naming rule proposed by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), could look like. The analysis illustrates how different interpretations may impact investment strategies and outcomes.

Disclosure and Naming Rules for Sustainable Financial Products and Funds

The EU’s SFDR has established three investment product categories, known as Article 6, Article 8, and Article 9, each with corresponding disclosure requirements. Providers of Article 8 and 9 products are required to disclose the (planned) asset allocation across investments which qualify as sustainable, with the expectation for Article 9 products that (almost) all assets qualify as sustainable. The SFDR defines a sustainable investment as “an investment in an economic activity that contributes to an environmental or social objective, provided that the investment does not significantly harm any environmental or social objective and that the investee companies follow good governance practices” (shortened version from Regulatory Technical Standards, Annex II – Full definition contained in SFDR article 2(17)).

In addition to the SFDR requirements, ESMA has proposed fund naming rules whereby funds with the word ’sustainable’ or any derived term in their name must allocate at least 50 percent of their investments to sustainable investments as defined by SFDR.

Questions remain as to how the SFDR’s definition for sustainable investment should be applied in practice and the European Supervisory Authorities have asked the European Commission to issue further guidance. The following analysis highlights the impact of different interpretations of the sustainable investment share within an investment product, using the STOXX Europe 600 as a sample.

Contributing to an Environmental or Social Objective

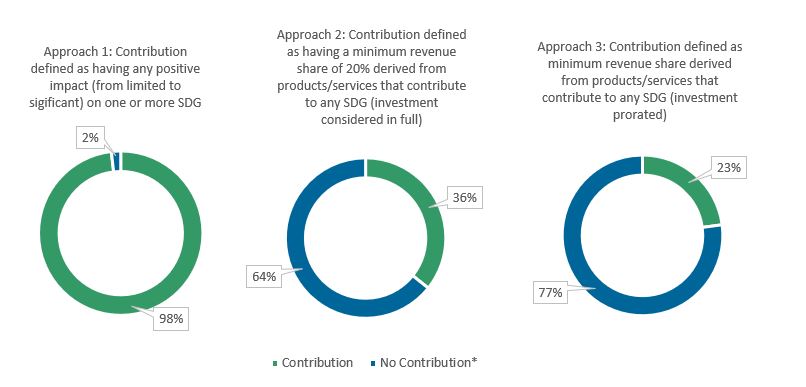

An investment’s contribution to an environmental or social objective could be identified by evaluating an investee company using a holistic rating system such as the ISS ESG Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Impact Rating (Figure 1, Approach 1). This approach assesses the company based on the impact of its products and services as well as that of its operations and management along the entire value chain.

The contribution could also be evaluated by looking at revenue streams to assess the impact of a company’s products and services; this can be done with the ISS ESG SDG Solutions Assessment. With this approach, an investment in an investee company might be considered sustainable in full if the company derives a minimum share of revenues from sustainable products or services (Figure 1, Approach 2). Alternatively, one could consider only a proportion of the investment sustainable (Figure 1, Approach 3) based on the revenue share derived from the contributing products and services.

Figure 1: Approaches to Assessing an Investment’s Contribution to an Environmental or Social Objective

*For this analysis, investments where no data was available (approximately 1.8% for all approaches) were considered to have no contribution to an environmental or social objective.

Source: ISS ESG

Not Causing Significant Harm

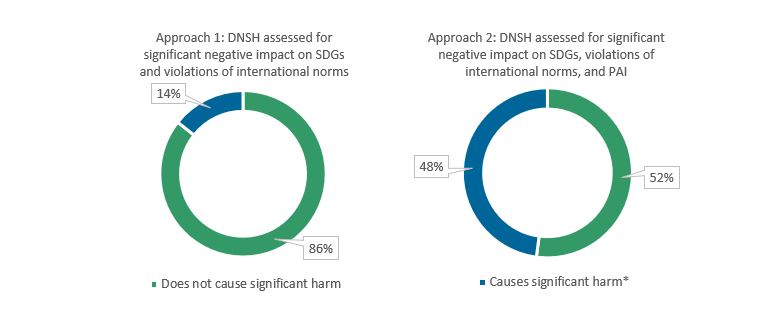

The SFDR also leaves open to interpretation how to apply the principle of ‘do no significant harm’ (DNSH). The Regulatory Technical Standards require that the statement of DNSH explains how the indicators for specific principal adverse impacts (PAIs) are “taken in into account” and how the investments align with the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Nevertheless, what exactly this requirement means remains unclear.

One approach to this requirement could be to consider as sustainable only those companies which, according to ISS ESG Norm-Based Research, do not breach international norms and have no significant negative impact on any of the SDGs according to ISS ESG’s SDG Impact Rating. This could be accompanied by disclosure on how investments perform in relation to the PAI indicators, as can be assessed using the ISS ESG SFDR Principal Adverse Impact Solution (Figure 2, Approach 1).

Another approach could be to place more emphasis on the PAI indicators and exclude from the sustainable investment share those companies with particularly high adverse impacts across the PAI indicators (Figure 2, Approach 2). However, a lack of disclosure means limited data is available for some PAI indicators. As a result, for this example, investments were deemed unsustainable if investee companies were found to cause significant adverse impact for a subset of PAI indicators, where data was sufficient to conduct a meaningful analysis.

Figure 2: Approaches to Assessing the ‘Do No Significant Harm’ (DNSH) Principle

*For this analysis, investments where no data was available for one or more factors were considered as causing significant harm. Approximately 1.8% of holdings for Approach 1 and Approach 2 were considered to cause significant harm due to a lack of data. For Approach 2, principal adverse impact (PAI) was assessed for primary corporate indicators only. Sufficient comparable data was available for the following indicators: GHG intensity, activity in the fossil fuel sector, non-renewable energy production, activity negatively affecting biodiversity-sensitive areas, violations of UN Guiding Principles or OECD Guidelines, lack of processes and compliance mechanisms for monitoring compliance with UN Guiding Principles or OECD guidelines, board gender diversity, and involvement in controversial weapons.

Source: ISS ESG

Complying with Good Governance Practices

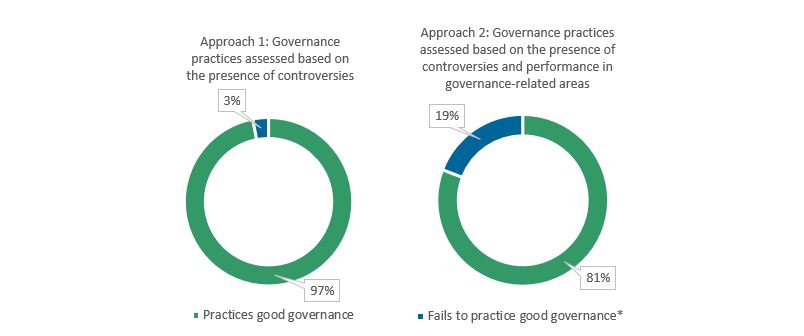

The last criterion for sustainable investment established by SFDR is that of good governance practices. While the European Commission has established that this is an indispensable consideration for both Article 8 and 9 products, how this requirement should be assessed remains open to interpretation.

The presence of good governance practices could be assessed by screening for involvement in controversies related to relevant areas based on ISS ESG’s Norm-Based Research (Figure 3, Approach 1). While this method would flag worst offenders, it would not necessarily assess the underlying policies and processes in place at investee companies. A more holistic approach would be to assess companies not only for governance-related controversies but also by leveraging the ISS ESG Corporate Rating to check to what extent companies have due diligence measures in place in areas related to corporate governance, business ethics, and staff (Figure 3, Approach 2).

Figure 3: Approaches to Assessing Good Governance Practices

*For this analysis, investments where no data was available (approximately 0.2% for Approach 1 and 1.8% for Approach 2) were considered as failing to practice good governance.

Source: ISS ESG

Conclusion

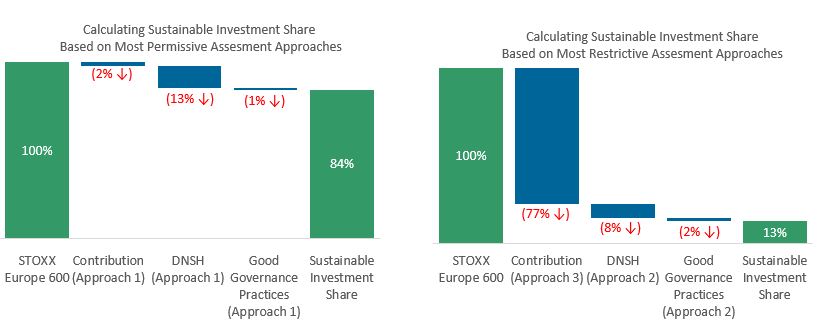

Combining the three steps of the analysis shows that – depending on the chosen approach – as much as 84 percent or as little as 13 percent of the STOXX Europe 600 could be considered “sustainable” within the meaning of SFDR. This finding has profound implications for retail investors and their financial advisors, fund managers, institutional investors, and the market

Figure 4: Combined Approaches to Assessing Sustainable Investment Share

Source: ISS ESG

Retail investors might find it difficult to interpret the minimum sustainable investment shares reported in pre-contractual and periodic disclosures. Further, fund managers choosing a more rigorous assessment approach may struggle to develop investment products with close to 100 percent sustainable investments – as prescribed for Article 9 products – or even comply with the proposed minimum share of 50 percent sustainable investments for funds marketed as sustainable. Although EU regulatory efforts aim to create a more standardized characterization of sustainable funds, ISS ESG’s analysis shows that interpretations of what constitutes a sustainable investment will likely vary. The outstanding response from the European Commission on the questions regarding the interpretation of Union law may provide additional clarity and hence improve comparability across financial market participants’ disclosures.

If regulators decide to restrict the range of possible interpretations of the sustainable investment definition, however, this might preclude some otherwise effective approaches to sustainable investing from achieving regulatory-defined thresholds. For instance, if a contribution could only be considered by using a prorated investment share approach (Figure 1, Approach 3), financial market participants would need to rely heavily on investments in pure players.

To avoid restricting financial market participants’ flexibility, another option could be to endorse a broad definition allowing for different interpretations and rely on transparency requirements instead of prescribing quantitative thresholds. This would enable product providers to communicate, within regulatory disclosures, the variety of sustainable investment strategies present in the market, while leaving it to investors to decide for themselves which approaches align with their own preferences.

As the EU’s sustainable investment framework is still relatively new and under constant development, the ISS ESG Regulatory Solutions team continues to monitor and respond to the evolution of sustainable finance regulation in Europe and beyond.

Explore ISS ESG solutions mentioned in this report:

- Financial market participants across the world face increasing transparency and disclosure requirements regarding their investments and investment decision-making processes. Let the deep and long-standing expertise of the ISS ESG Regulatory Solutions team help you navigate the complexities of global ESG regulations.

- Identify ESG risks and seize investment opportunities with the ISS ESG Corporate Rating.

- Assess companies’ adherence to international norms on human rights, labor standards, environmental protection and anti-corruption using ISS ESG Norm-Based Research.

- Understand the impacts of your investments and how they support the UN Sustainable Development Goals with the ISS ESG SDG Solutions Assessment and SDG Impact Rating.

By: Lorna Parkinson, ESG Methodology Specialist – Regulatory Solutions, ISS ESG

Zahra Hashemzadeh, ESG Methodology Specialist – Regulatory Solutions, ISS ESG

Mathilde Krief, ESG Product Manager – Regulatory Solutions, ISS ESG

Ronja Wöstheinrich, ESG Methodology Lead – Regulatory Solutions & Fixed Income, ISS ESG

Karina Karakulova, Director of Regulatory Affairs and Public Policy, ISS