The Conference of the Parties (COP) climate change meetings have taken place for the last 20 years, and now represent the largest annual conference held by the United Nations. The COP meetings involve negotiations on the implementation of global climate change agreements, and include representation from governments across the world, as well as representatives from other stakeholder groups such as civil society and industry. The COP discussions have a significant impact on the way global business is done, and so are keenly watched by investor and business groups alike.

This year’s COP27 took place in November in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt. Proceedings were closely watched by Institutional Shareholder Services, and the following reports have been prepared by the ISS ESG & ISS Corporate Solutions business units:

- From Pandora’s Box to Missed Opportunities – A Tale of COP27: Key Takeaways for Investors from COP27; and

- Governments Stall, Corporates Forge Ahead: Key Takeaways for Companies from COP27.

Key Takeaways

- Mitigation

- Governments at COP27 showed a lack of ambition, failing to reach an agreement on further action to mitigate emissions.

- While COP27 failed to establish stronger mitigation commitments, market trends and stakeholder expectations – including those of investors, business partners, and regulators – show that companies continue to set increasingly ambitious emissions reductions targets and are implementing more concrete action plans.

- Loss and Damage Fund

- Delegates agreed to create a specific fund to compensate vulnerable countries for irreversible damage caused by climate change.

- The agreement on the loss and damage fund may affect corporate expectations regarding environmental justice.

Last year’s COP26 concluded with the signing of the Glasgow Climate Pact by 197 countries. The pact reaffirmed the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting temperature rises to 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels, with pledges from signatories to further cut their greenhouse gases emissions.

This year’s COP27, which took place from November 6 to 18, adopted the slogan “Together for Implementation” to stress the importance of translating existing commitments into credible action plans that will keep the 1.5°C goal within reach. This objective was not achieved, however, as no stronger commitments to the Glasgow Climate Pact were included in the Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan. Proposals to reduce reliance on fossil fuels (building on last year’s agreement to phase down the use of coal) fell apart, as they were met with significant opposition from oil-and-gas producing countries.

Despite the failure to tackle climate change mitigation, the parties agreed to a momentous deal to create a Loss and Damage Fund that will require developed countries – which are the most responsible for historical emissions – to provide compensation to vulnerable developing countries that are already suffering the most from climate-change related disasters.

These two developments – the lack of stronger commitments on emissions reductions and a deal to create a Loss and Damage Fund – are the main takeaways from this year’s COP27. In the following sections, we will expand on their implications for corporate issuers. For insights into the implications for investors, please see this companion piece.

Mitigation – Corporate Momentum Continues Despite Limited Intergovernmental Progress

Expectations for action on mitigation were high for COP27, especially as it was framed as the “Implementation COP,” one that would seek to solidify action to keep the 1.5°C goal achievable. Specifically, there were calls for more concrete follow-through on the phase down of coal, a commitment to expand the phase out to all fossil fuels, including oil and gas, and a resolution to reach peak emissions by 2025. However, the Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan largely sticks to the language in the Glasgow Climate Pact, promising to accelerate, “efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.”

Some progress was made on mitigation and emissions reductions elsewhere. The “mitigation work program,” whose aim is to scale up mitigation ambition and implementation, was finalized. However, some parties said the program weakened some existing commitments. For example, the work program cannot impose new targets or goals on emissions reductions. The global methane pledge, which aims to reduce emissions of the gas by 30 percent by 2030, gained momentum. First launched at COP26 with 80-100 signatories, the pledge now has 150 signatories, including Australia, Egypt, and Qatar.

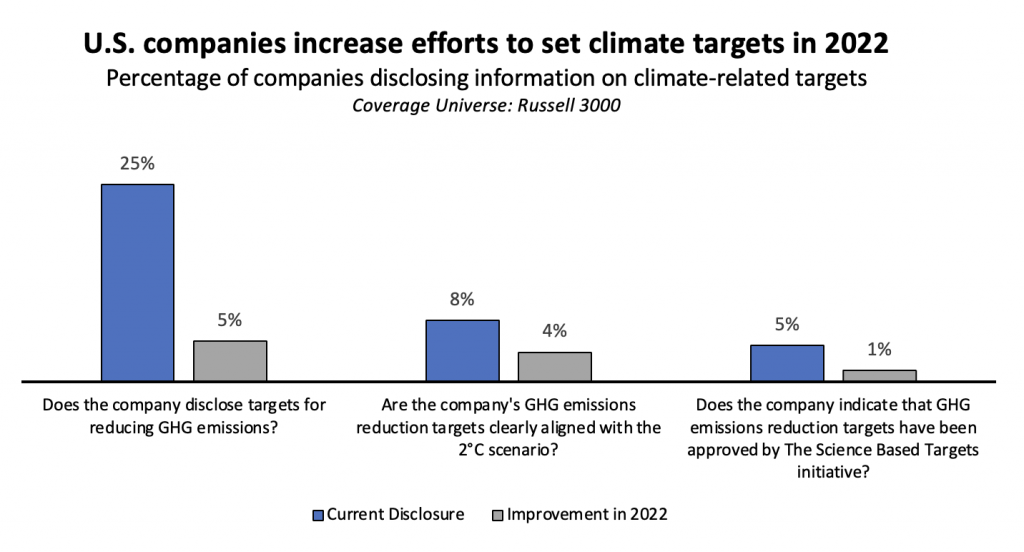

The limited progress on mitigation at COP27 should not discourage corporates from pursuing their climate change strategies and Net-Zero goals. ISS Corporate Solutions (ICS) analysis found that 25 percent of companies in the U.S. disclosed targets for reducing GHG emissions as of September 2022. Encouragingly that’s up from 20 percent in 2021, with 5 percent of the total making disclosures for the first time this year. Similarly, while only 8 percent of companies in the U.S. have aligned their targets with the 2°C scenario, half of those companies aligned between 2021 and 2022.

Source: ICS Analytics, Environmental & Social QualityScore Data

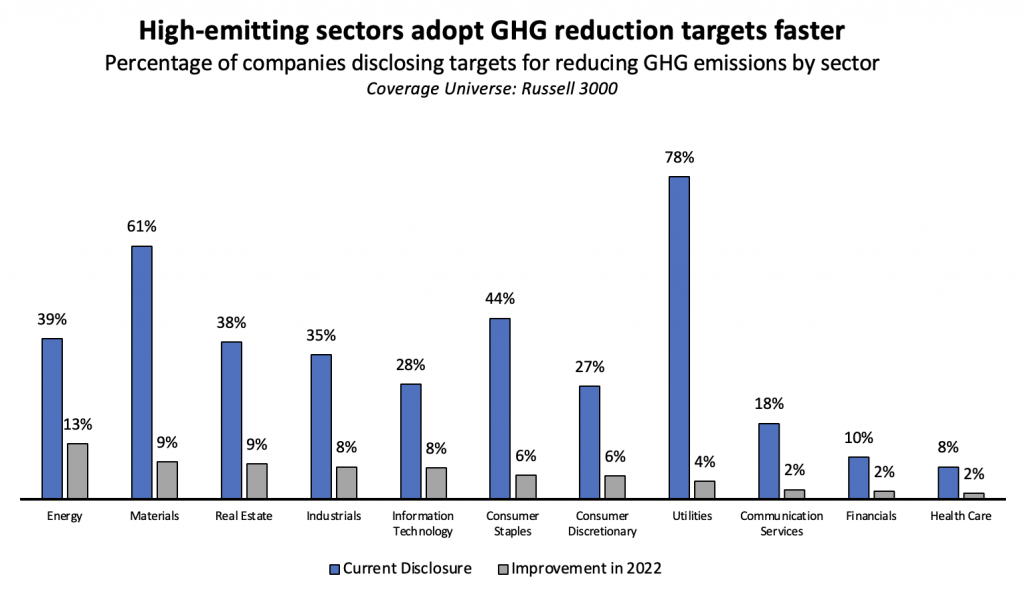

A breakdown by sector provides more details on corporate GHG emissions reduction targets. High-emitting sectors with the highest exposure to climate impacts appear to be accelerating their efforts. An ICS analysis of Russell 3000 company disclosures shows that 13 percent of companies in the Energy sector disclosed GHG emissions targets for the first time between 2021 and 2022. That compares with 9 percent in the Materials sector, and 8 percent in the Industrials sector. This increase in disclosure is significant given that each of these sectors make significant contributions to global GHG emissions.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2022 report on mitigation, 34 percent of total net anthropogenic GHG emissions came from the energy supply sector and 24 percent came from industry (IPCC’s report does not use the GICs sectors, but its industry categorization combines the GICs Materials and Industrials sectors). The Utilities sector is also considered a high contributor to GHG emissions, as it belongs to the IPCC’s energy supply sector category. However, while 78 percent of companies in the Utilities sector are already disclosing GHG emissions reduction targets, only 4 percent of utilities companies under coverage disclosed targets for the first time in 2022.

Source: ICS Analytics, Environmental & Social QualityScore Data

The analysis demonstrates that momentum for setting GHG emissions reduction targets continues to build amongst U.S. companies, especially in the sectors associated with higher levels of direct emissions. While COP27 failed to establish stronger mitigation commitments, market trends and expectations of stakeholders – including investors, business partners and regulators – point to companies continuing to set more ambitious emissions reductions targets and implementing more concrete action plans.

Loss and Damage Fund – A Bellwether for Environmental Justice

After many twists and turns in the discussions, the 197 “parties” (i.e., countries) present at COP27 agreed to establish a Loss and Damage Fund to help vulnerable countries most affected by climate change recover from climate disasters.

As explained by the Australian organization the Climate Council:

“loss and damage funding refers to finance that directly addresses unavoidable climate change catastrophes that developing countries are particularly vulnerable to.”

This funding could for instance be allocated for the reconstruction of homes and infrastructure after a climate-related disaster. That is different from climate finance, which refers to:

“developed countries giving money to help developing countries build clean energy systems, reduce emissions, and cope with the overall impacts of climate change.”

An agreement to create a loss and damage fund at a U.N. climate summit is a major change because developed countries have resisted the idea for decades, citing concerns that they would be held legally liable for historic emissions. The deal includes language to quell these concerns and, more importantly, sets the stage for parties to figure out exactly how the fund would work: which countries would pay, how much they would pay, and which developing countries would be eligible to receive the funding. These details are set to be formalized at next year’s COP28 in Dubai.

The deal to create a loss and damage fund also highlights and reinforces the emerging topic of environmental justice. The United Nations Development Program (UNDP) “conceptualizes environmental justice (including climate justice) as promoting justice and accountability in environmental matters, focusing on the respect, protection and fulfillment of environmental rights and the promotion of the environmental rule of law.” The loss and damage fund aligns with the concepts of accountability and justice, setting the expectation for the Global North to be held responsible for its impacts on the Global South. The development is a major signal to corporates that expectations regarding environmental justice are likely to increase in the future.

Currently, corporate expectations for environmental justice remain in their infancy, as only a handful of companies currently explicitly reference environmental justice in their disclosures, and relevant reporting standards have not been firmly established. The COP27 decision to create of a loss and damage fund will likely spur relevant stakeholders to formalize expectations on environmental justice.

Conflicting Signals Lead to Risks and Opportunities for Corporates

International agreements and commitments represent incremental progress and may also signify directional trends in policy. Despite limited progress on mitigation at COP27, stakeholder expectations related to climate change continue to rise for companies, as indicated by increased efforts to adopt GHG emissions reduction targets across multiple sectors.

While mitigation efforts at the intergovernmental level may have slowed down, the timeline for addressing climate change remains urgent. Failure to set clear and actionable climate objectives at the corporate level may exacerbate the risk of a disorderly transition. While companies are compelled to continue to manage climate change risks, the establishment of a loss and damage fund may also create new opportunities for positive impact in relation to environmental justice and other areas.

By: Dennis Tung, Sr. Associate, Sustainability Advisory Group Manager, ISS Corporate Solutions