The modern economy largely follows a linear system: we design products that ultimately become waste. Oftentimes the use of toxic chemicals in the form of (for example) adhesives, binders, or antioxidants, inhibits a possible reuse of products at their end of life, and we are left with no choice other than incineration. As an example, several decades ago the printed IKEA catalogue was found to contain around 90 substances of concern to human health or the environment. This number has since dropped to 50, an improvement but still a number that renders the paper in the catalogue unsuitable for composting and prevents the material from staying ‘in the loop’.

This and other examples demonstrate the importance of material health and the selection of chemicals when designing products for circularity. As part of the ISS ESG Circular Economy series, this paper explores the risks and opportunities associated with material health, and highlights the dormant potential of corporate strategies for the reduction of substances of concern in products.

The Cradle to Cradle Products Innovation Institute describes the concept of material health as follows:

“Chemicals and materials used in the product are selected to prioritize the protection of human health and the environment, generating a positive impact on the quality of materials available for future use and cycling.”

Various important commitments are required to achieve this goal, including:

- Avoiding the use of organohalogens and the use of other toxic substances, e.g., those included in the Cradle to Cradle Restricted Substances List and/or ChemSec’s SIN List;

- Knowing which chemicals the product consists of and is in contact with during the production process;

- Assessing the substances’ compatibility with human and environmental health;

- Establishing a roadmap towards prioritizing the application of substances that are assessed as compatible with human and environmental health;

- Use of safe chemicals;

- Ensuring indoor and outdoor air quality and the health of employees and consumers/users; and

- Refraining from using hazardous substances in the supply chain.

Substances of concern play a crucial role in a circular economy. According to the UN Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEPFI):

“Every product is made out of chemicals so the chemical sector rightly calls itself the ‘industry of industries’.”

The true secret of circular product design is that you can only make the right decision on material and chemical ingredients if you know what the product’s next life will look like. To illustrate: it is estimated that 98% of plastics are not recycled into a closed loop system, and that more than 14 million tons of plastic end up in the ocean. This represents not only a massive loss of materials, it also causes significant harm to the biosphere.

At first sight, it may seem like a good idea to collect this ocean plastic and use it to manufacture packaging, for example in cosmetic products. This is easier said than done, however – the ocean plastic may contain harmful chemical ingredients that are emitted into the cosmetic product itself, which are then applied on human skin in form of a creme or shower gel. Without knowing that used materials are free from hazardous substances, these cannot serve as input materials for many new products. End-of-life solutions are not always the answer – more effective solutions can be found in the design phase.

As pointed out by the International Chemical Secretariat, hazardous substances tend to accrue if continuously recycled and, in turn, will remain in use for a long period, despite having been potentially prohibited for use in new products in the meantime. This demonstrates the importance of determining in the design phase what the product’s next life is going to be, and selecting safe chemical ingredients accordingly. It is this sort of thinking that differentiates the circular economy from the recycling economy.

Win-Win: Improved Material Health Keeps Materials in the Loop and Reduces Community Health Risks

The creation of new jobs is often cited as the positive social impact in the context of a circular economy. According to the ILO, a transition to a circular economy could generate between seven to eight million jobs by 2030 worldwide. Apart from employment, a true circular economy that considers material health in the design phase has the power to have further positive social impacts: by relying on healthy materials, consumer health as well as the health of employees in the production process can be assured.

One product group which can have a significant impact on consumer health is interior fittings. In the 1980s and ‘90s, Ikea was facing scandals regarding some of its products that released formaldehyde fumes above legally permitted thresholds. Formaldehyde is known for its adverse effects on human health when certain thresholds are exceeded. It can cause irritations to skin, throat, nose, and eyes, and may even cause cancer. The Swedish furniture retailer responded positively to this issue and has been reducing formaldehyde emissions from its products ever since, but formaldehyde can also be found in flooring, house insulation material, tobacco smoke, candles, disinfectants, cosmetics, and textiles. Leading manufacturers are not only refraining from using hazardous substances, they are developing products with a positive impact. For instance, a carpet manufacturer offers carpet tiles that do not release toxic fumes, and actually improve indoor air quality.

Regulators are Stepping Into the Arena, but a Broad Corporate Response is Yet to be Unlocked

Chemical regulation may not be front page news, but regulatory pressure is growing, particularly in Europe. The European Commission acknowledges the importance of the chemical industry on circularity, for example as part of the European Circular Economy Action Plan which forms part of the European Green Deal. Moreover, the EU’s chemicals strategy for sustainability towards a toxic free environment aims, among other goals, to ban harmful chemicals from consumer products.

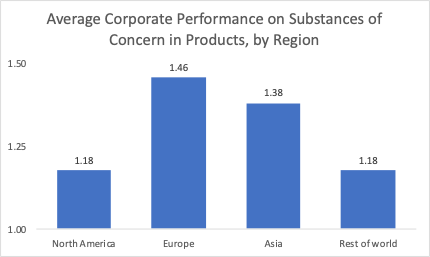

At a global level, the next International Conference on Chemicals Management (ICCM5) is going to address global action on safe chemical use beyond 2020. In the past, governments had committed to reduce the hazards of chemicals by 2020. Manufacturing that uses only safe chemicals is still a far-off ambition, but substances of concern have made it onto the agenda of legislators. An analysis of ISS ESG data shows that companies in jurisdictions with more advanced chemicals regulation also show a better performance related to material health. The ISS ESG Corporate Rating assesses companies’ performance on the use of substances of concern on a scale from 1 (worst) to 4 (best). It is evident from this data set that European companies are on average more advanced than their peers in other regions of the world, although Asian companies are catching up.

Source: ISS ESG Corporate Rating (as of January 2022)

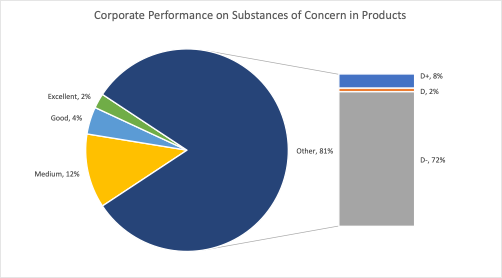

The potential hazards stemming from the use of substances of concern are gaining attention, as are the impediment these represent for the transition to a circular economy. ISS ESG data shows that corporate action on the matter is still lagging, however. As demonstrated in a previous analysis by ISS ESG, the vast majority of chemicals companies in the ISS ESG universe underperform when it comes to appropriate chemical management, and a similar picture emerges when looking at a broader set of sectors.

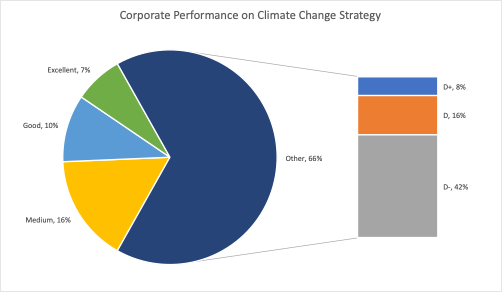

This deficit becomes most apparent when the issue of chemical use is contrasted with more front page ESG matters such as climate change. While in both areas a majority of companies are assessed as having an overall ‘Poor’ performance, strategies to reduce climate impacts are more prevalent than systematic approaches to phasing out the use of substances of concern in products. In fact, over 70 percent of companies whose approach towards substances of concern in products was assessed by ISS ESG’s Corporate Ratings team were found not to report on any relevant policies or measures (assessment result: D-), while this only holds true for 42 percent of companies when it comes to climate change strategies.

Source: ISS ESG Corporate Rating (as of January 2022)

Unleashing the potential of a circular economy

As the Ellen MacArthur Foundation points out, only 55 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions can be addressed by improving energy efficiency and switching to renewable energies. Tackling the remaining 45 percent requires the adoption of circular economy practices. To unleash this tremendous potential in addressing the ‘overlooked emissions’ and tap into the economic opportunities that come with a transition to a circular economy, a greater emphasis on material health is necessary. ISS ESG data allows investors to evaluate which companies are acting on reducing the use of substances of concern in products and improving material health.

Explore ISS ESG solutions mentioned in this report:

- Identify ESG risks and seize investment opportunities with the ISS ESG Corporate Rating.

By Ronja Wöstheinrich, Associate Vice President, ESG Methodology, ISS ESG.

Hanna Taya, ESG Rating Analyst, ISS ESG.