In 2010, ISS ESG’s head of Climate Solutions Max Horster started one of the first companies to measure the impact of climate change on investments. From investment carbon footprinting to climate scenario analysis, from climate-linked proxy voting to climate neutral investments via offsets: over the years, the team pioneered a wide range of today’s leading methodologies and approaches across all asset classes. In 2017, Max and his team joined ISS ESG to form the first climate specialist unit of a global ESG service provider. Today, they cover over 25,000 issuers on up to 600 individual climate-linked data points and have screened over USD 4 trillion of AUM on their climate risks and impact. On the occasion of its 10th anniversary, the ISS ESG Climate Team shares 10 lessons from 10 years of helping investors to tackle climate change.

Lesson 9: Bad Boards Are Elected by Good Investors Who Don’t Vote*

Abraham Lincoln is reputed to have said: “The ballot is stronger than the bullet.” This axiom has held in subsequent years. The history of voting in politics is often considered to have largely decreased armed conflicts, supporting innovation and wealth creation in ever more stable societies. For investors globally, however, voting the stock of companies that they own at annual general meetings (AGMs) is still often a topic of hemming and hawing.

This is important. When you own shares in a company, you become a part owner of that company, and therefore have the right – and many argue the responsibility – to influence the direction of the company by voting your shares at the company AGM each year. Because most investors aren’t able to attend company meetings in person, they are able to indicate their intentions via a ‘proxy vote’ cast remotely, often via a service provider such as ISS Proxy Voting Services. While most votes are carried with large majorities in line with management’s recommendations, controversial AGM resolutions can be quite tight, particularly on matters relating to environmental or social matters. So every vote counts!

Climate Change has real potential to move the needle. After all, investors are being expected to do their part in addressing global warming. When it comes to listed equities, divesting will not have the real-world outcome of decarbonizing the economy that civil society and politics are after. Investors need to make use of their power to nudge companies toward higher climate resilience and positive climate impact. This works through engagement and voting.

Climate Engagement: A Toothless Tiger?

The most prominent and potent collective climate engagement initiative is surely Climate Action 100+: This investor coalition was launched in 2017 and combines 570 investors with nearly $55 trillion in assets under management. Together, they lobby approximately 160 of the largest greenhouse gas emitters to align with the goal of the Paris agreement: limiting global warming to below 2 degrees Celsius. So many investors and so much money! Climate Action 100+ should be the litmus test for the success of climate engagement.

There have been a range of pledges and joint statements, such as from Royal Dutch Shell, Maersk and Duke Energy. Given the urgency of the challenge and the investor power focused on addressing it, however, the results are quite sobering. A recent progress report from March 2021 revealed that, despite a number of net zero pledges, none of the focus companies have scored top marks, none have fully disclosed strategies, nor have they aligned future capex with net zero targets.

The reactions were immediate and fierce. Brynn O’Brien of the Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility commented on the results suggesting they were “cast iron proof that the world’s largest emitters are failing to materially rein in their impact on the planet, and that investor strategies to engage them have not yet risen to the challenge”. Climate campaign Follow This has described companies’ CA100+ statements as “a fig leaf to hide inaction”.

Voting: Putting Teeth Into the Tiger

So, has Climate Action 100+ failed? Not yet, but it is high time to put teeth into the investor’s tiger before it’s seen as a harmless kitty. This is where shareholder votes come in.

“We expect that in 2021, CA100+ will endorse its members’ use of all tools in the investors’ toolbox, including voting” stated Mark van Baal, the Founder of Follow This, in reaction to the CA100+ progress report. “We hope CA100+ investors will follow this up with votes in favor of climate resolutions at annual meetings, as that is the only thing boards listen to. (…) We don’t have time for another round of discussions.” In other words, if investors are serious about addressing climate change, engagement is a starting point, but as soon as the outcomes plateau and the results don’t keep up with the speed of change needed, engagement needs to be followed by voting.

Climate Voting the Way You Like It

There are three main approaches to utilizing the power of shareholder votes to address climate change:

1.) Climate Shareholder Resolutions: Baby Steps Into the Right Direction

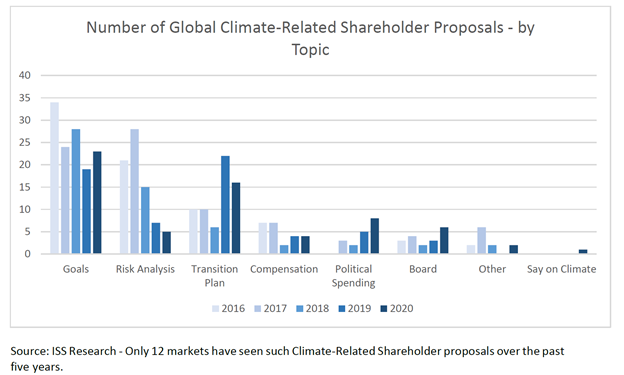

Shareholder resolutions on the topic of climate change are evolving rapidly – and so are their focus. While the past 5 years saw investors predominantly target climate risk disclosure, more recently the focus has switched to wanting to see climate strategies. In the latest ISS review on Climate and Voting, this shift is quite visible based on global data:

Are shareholder resolutions the solution to driving progress towards a climate friendly economy? They certainly make a contribution, but they are too few and too unsuccessful to rest investor’s climate responsibility on them. In 2020, only nine markets (Australia, Canada, France, Japan, Norway, South Africa, Spain, the United Kingdom and the U.S.) saw climate-related shareholder resolutions – mostly targeting Banking, Oil & Gas as well as the mining sector. In total, there were less than 50 such resolutions and only 11 received majority support.

2.) Say on Climate: Learning to Walk Properly

More recently, with the first proposal seen in 2020, proponents have requested companies to publish their climate action plans and submit them to a shareholder vote on an ongoing annual basis. Borrowed from the popular “Say on Pay” shareholder proposals in many markets, this momentum has been termed “Say on Climate” and is growing quickly in popularity.

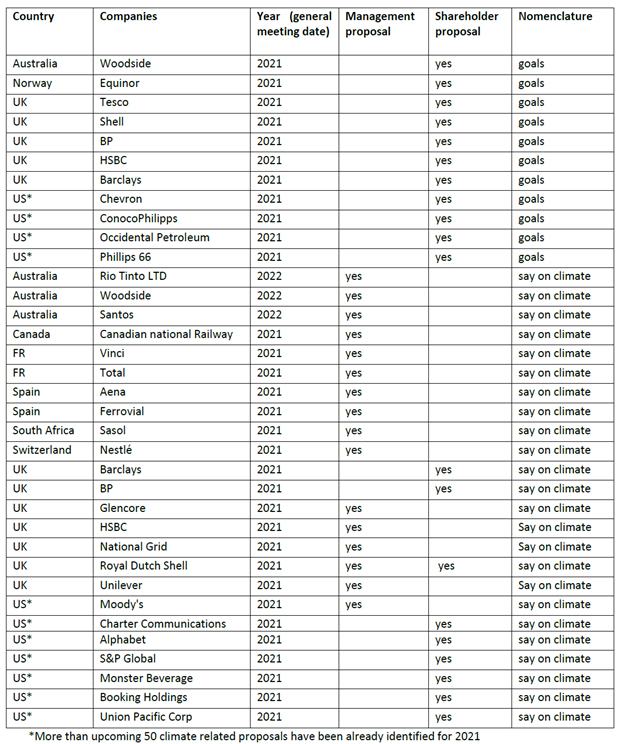

Several companies have already agreed to feature this in their annual voting items. The one “Say on Climate” proposal that was put to vote in 2020 at Aena in Spain saw high levels of support (likely because it was also supported by management). ISS Governance data from March 2021 identifies 24 “Say on Climate” proposals out of the over 50 upcoming climate-related shareholder proposals for 2021:

Source: ISS Governance Insights, “Climate & Voting: 2020 Review and Global Trends,” 2021.

Both general climate-linked shareholder resolutions as well as “Say on Climate” resolutions put a spotlight on companies’ climate strategies. Given the magnitude of a challenge like climate change, however, they are unlikely to reach the necessary volume soon enough. There are also prominent voices in the market that criticize “Say on Climate” for “rubberstamping” inadequate climate strategies and taking the necessary heat away from directors. More often than not, though, there simply is no climate change ballot item at all. To overcome this, investors need to vote on climate without waiting for climate to appear on the agenda.

3.) Climate Voting Policies: The Sprint Towards the Common Goal

Imagine a shareholder unhappy with an investee company’s climate performance, but without a climate shareholder resolution to make these concerns heard in the boardroom. To address this all too common situation, ISS came out in 2019 with a climate voting offering. It allows investors to vote on regular ballot items such as the (re-) election of directors, using a climate concern lens.

If a company does not meet the climate expectations of the investor, the investor might make their voice heard in the boardroom by voting against management on regular standard voting items. The vote is not ON the climate strategy, but BECAUSE OF the climate strategy (or lack thereof).

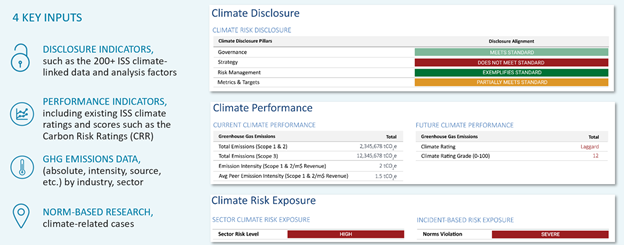

In order to do this, however, the investor needs access to quality, timely and comparable information on the climate performance of listed companies. To this end, ISS ESG has developed the climate awareness scorecard that measures company progress on:

- climate transparency on climate governance, risk management, strategy, and metrics & targets – the four pillars from the Task Force on Climate Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD);

- climate performance today (measured as greenhouse gas emissions per revenue versus peers) and in the future (using a bottom up analyst-driven Carbon Risk Rating that judges the climate change preparedness of a company);

- Climate norms violations including lobbying against climate action; and

- the sector-linked climate risk that a company is exposed to.

Source: ISS Climate

So, if a company in a high-risk sector remains opaque about its climate strategy or does not transition in line with the investor’s expectation, the investor votes against the board and management’s recommendations. Although still nascent in the market, this tried and tested approach can play out extremely powerfully if investors with a climate agenda – such as Climate Action 100+ signatories – adopt it.

The Bullet Versus the Ballot

Most of an equity and fixed income investor’s climate action is still defaulting to a form of divestment, which as we have noted previously can be a blunt instrument. It arguably makes a portfolio more resilient without impacting the real economy.

A publicly announced divestment by a prominent investor might send a signal to the divested company to change course, but it is a one-time shot from a gun with only one bullet in the chamber. Once this bang has faded, the impact has as well.

The ballot, on the other hand, is a constant opportunity for driving change if and when investors apply it consistently. Whether by supporting AGM resolutions, joining industry-wide initiatives like “Say on Climate”, or using the power of a shareholding to express a lack of confidence in climate-laggard directors and company management.

Good investors own bad companies. This can be a good thing, so long as the investors act on their knowledge. After all, bad boards are elected by good investors who don’t vote. Lincoln would give voting an “Aye”.

*Not (yet) a proverb but based on one: “Bad officials are elected by good citizens who don’t vote”.

By Dr. Maximilian Horster, Head of Climate Solutions, ISS ESG