In 2010, ISS ESG’s head of Climate Solutions Max Horster started one of the first companies to measure the impact of climate change on investments. From investment carbon footprinting to climate scenario analysis, from climate-linked proxy voting to climate neutral investments via offsets: Over the years, the team pioneered a wide range of today’s leading methodologies and approaches across all asset classes. In 2017, Max and his team joined ISS ESG to form the first climate specialist unit of a global ESG service provider. Today, they cover over 25,000 issuers on up to 600 individual climate-linked data points and have screened over $4 trillion of AUM on their climate risks and impact. On the occasion of its 10th anniversary, the ISS ESG Climate Team shares 10 lessons from 10 years of helping investors to tackle climate change.

Lesson 7: Regulation and Climate Change: The Tragedy of the Misled Theory of Change

In late 2017, the European Union set out to use its regulatory power in financial markets to address climate change. The aim was nothing less than ensuring that the EU finance industry would play its part in helping the EU achieve its climate goals. The outcome, however, is a tragedy of the theory of change. Great intentions and enormous efforts have met with a poor understanding of financial market mechanics. The result will have a big impact on the financial industry, but it may have hardly any impact on climate change.

Matching the tool to the task

One basic theory of change behind ESG investing is that the financial industry can impact the real economy for positive environmental and social outcomes. In the area of climate change, for example, many see investors as a key lever in decarbonizing the economy. Sustainably managed asset levels are moving from one high to the next, the European Union has set out to “green” the financial markets, green bonds are reaching record volumes, and hundreds of investment houses globally have joined collective climate engagement initiatives such as Climate Action 100+.

Considering these trends, one may conclude that the financial industry is doing its part to prevent the most catastrophic consequences of climate change. Global greenhouse emissions remain stubbornly unimpressed by these regulatory and investor initiatives, however, and keep increasing to unprecedented levels, a temporary slow-down due to the COVID-19 pandemic notwithstanding.

One wonders why we do not see a reversal in emissions despite global efforts on the investment front. Is the financial system too slow to counter the accelerating emission of greenhouse gases? Or is there a fundamental flaw in the theory of change that a lot of ESG investing is based on? Are we using the right tools for the job?

Divestment can be a blunt instrument

The amount of money managed sustainably is breathtaking to those of us who have been in the sector for a long time. It is, however, important to note that not all of the investments that are being managed sustainably share the intention of creating of positive impact. Increasingly, ESG analysis is seen as addressing and measuring material risks that should matter to any investor. The exposure to companies that emit large amounts of greenhouse gas emissions should be of concern for any investor who expects politics to introduce a price on carbon, as that might negatively impact financial returns. Avoiding investment in such companies can enhance existing risk measurement frameworks, which may result in an internal re-allocation of capital and help generate alpha.

Such an exclusionary approach helps investors to reduce their portfolio exposure to climate risks. Given that stock markets are secondary markets, however, such a de-risking does not necessarily result in an impact on the real economy – the sources of ESG risk will most likely continue to exist.

One of the most common exclusion topics exists around weapons. However, by not investing in stocks of weapon companies, investors are not reducing the amount of weapons in the world, and weapon manufacturers do not go out of business. The same is true for climate change. By divesting from fossil-fuel companies or high carbon emitters, those companies do not go out of business. On the contrary, a divestment is only possible if another investor buys the stocks from the divesting investor.

A further iteration of this theory of change is that, if enough investors divest, a company will change course, as the share price drops to levels that will impact the business. This isn’t necessarily the case, however – even if the share price drops due to a global divestment, a company need not cease its business activities. The company may be undervalued, and management might simply buy back shares or even take the company private.

Overall, not investing in a company on the secondary markets of equities and bonds has very little impact on the real economy, but it does reduce an investor’s exposure to that asset. Divesting or reducing exposure to a certain company is therefore an appropriate risk management approach. Divestment is a less effective way to create a real impact, however. In other words, divesting is a good way to decarbonize a portfolio, but divestment does not decarbonize the economy.

So, what is a regulator to do?

At the moment, the world’s most active climate regulators are in Europe. Their focus has tended to be on transparency, and EU initiatives can be grouped under five broad headings:

- Mandating climate risk disclosure in the investment process;

- Mandating climate risk disclosure towards retail investors at the point of sale;

- Devising a taxonomy defining what type of companies are ‘sustainable’ or ‘green’;

- Introducing standards for green bonds and a label for green funds; and

- Developing a series of climate benchmarks that only sustainable or green companies can join.

The logic of the regulation is that an increase in transparency internally and towards stakeholders will help finance climate-friendly companies and withdraw financing from companies harming the climate. While the first part – creating transparency – will be helpful and effective in de-risking portfolios vis-à-vis climate change implications, it will not necessarily help funnel money from climate-harming to climate-friendly economic activities.

The EU focuses predominantly on equities, an asset class that does not have a direct and efficient impact on the real economy. Equities are traded in secondary markets, so the money that investor ‘A’ pays for a stock goes to investor ‘B’ who sells that security, and not directly to the company for its operations. So, by better understanding a company’s sustainability profile and (not) investing in it on these grounds, that company will neither disappear nor receive a boost. The regulatory efforts, not able to differentiate between cause and effects in public markets, fail to achieve their goal. Climate change will not be directly impacted by these approaches.

At this point, one might conclude that public equity investors are not able to impact the real economy, because they are operating in secondary markets. The opposite is true, however. Equity investors can efficiently change the course of a company by making use of informal as well as institutionalized approaches to ensure the investor’s voice is heard in the company’s boardroom. Engagement with the executives of a company that is not aligned with investors’ climate change expectations may prompt them to adopt a climate change strategy. This carrot can be complemented with the stick of proxy voting – if the engagement endeavor fails to achieve an adequate outcome, an investor can vote against the company’s management or remuneration plans at the next annual general meeting.

Re-thinking the toolbox

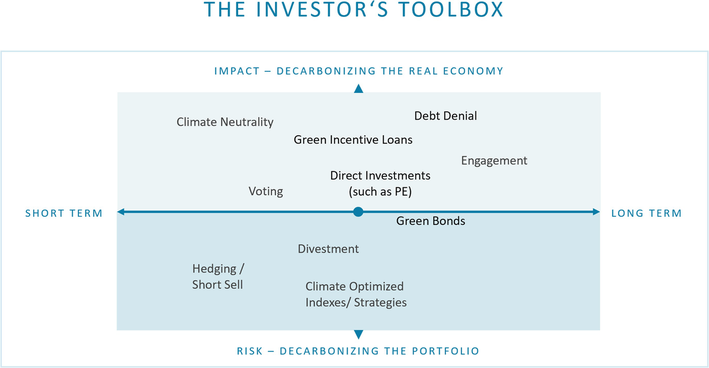

Financial market participants can efficiently change the course of companies. What is needed, though, is a more nuanced, asset class-specific approach that understands the respective dynamics as well as the available instruments in the ‘Investor’s Toolbox’.

Figure 1: The Investor’s Toolbox

Some of the tools at hand are geared towards decarbonizing a portfolio (lower part of Fig. 1), while others aim to decarbonize the real economy (upper part). For equities, approaches such as divestment and climate-optimized equity strategies can help from a risk management angle. Engagement and proxy voting can change the course of a company, however. On the debt side, not participating in the issuance of bonds or not lending to certain companies due to their ESG performance is an effective means of impacting economic activity and providing cheaper capital to companies that achieve certain ESG targets (for example through positive incentive loans).

The finance industry has very good intentions when it comes to solving the climate change challenge. In terms of approaches and execution, however, the nature of financial market mechanics may result in a lot of action without real impact. Only by making use of the entire investor’s toolbox, and by systematically and clearly evaluating the effects of each approach, can investors and regulators alike execute on their respective theories of risk or change.

Here are a few overlooked levers that might help the EU to turn its theory of change into real economic impact:

- Mandatory engagement and voting linked to climate issues.

- Rules on debt financing for climate-harming or -helping technologies and companies (green lending).

- Push for ‘Green Bond 2.0’ approaches such as positive incentive or penalizing bonds that require an issuer transition.

- Linking to other EU instruments such as the CDM mechanism in the EU Emission Trading Scheme to allow for portfolio climate neutrality at the cost of reducing emissions elsewhere.

- Enabling Net Zero investments that result in a Net Zero real economy, rather than in sophisticated but low-impact calculations on portfolios.

A more differentiated understanding of financial mechanics across asset classes will help the regulator to achieving the intended outcome that the current regulatory assortment is likely to miss: real world change.

By Dr. Maximilian Horster, Head of Climate Solutions, ISS ESG