At the close of the June main Japanese proxy season when two-thirds of Japanese companies hold their annual meetings, ISS found another uptick in board independence and female board representation.

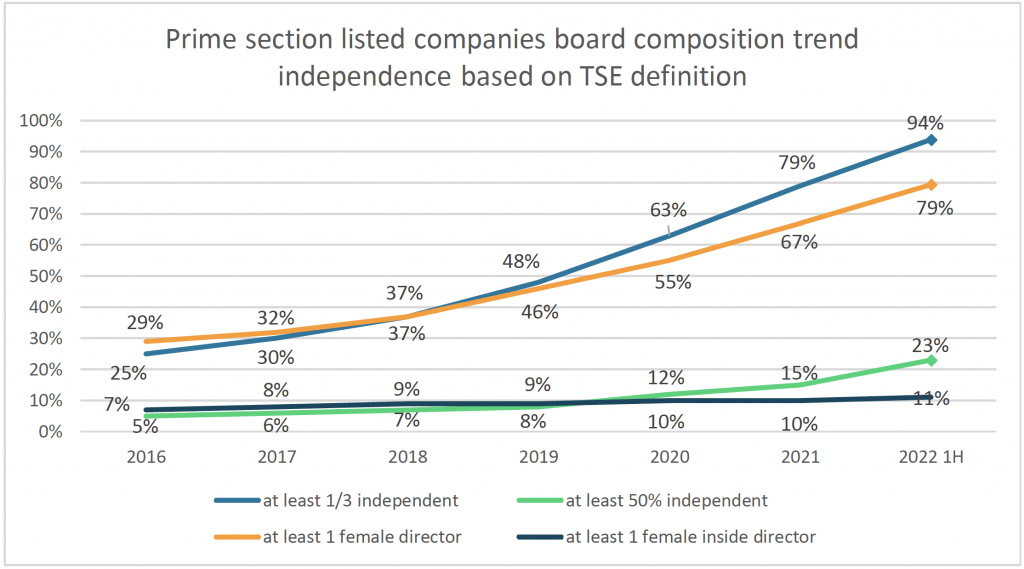

Based on companies that held their AGMs in the first half of 2022 (which represents more than 85 percent of Japanese listed companies), ISS found a 15-percentage point jump in companies with at least one-third independent boards (based on the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) classification), and a 12- percentage point increase in boards with at least one female director for companies listed on TSE’s Prime (the former First) listing section, compared with as of December 2021.

Based on the 1500+ companies listed on the TSE’s Prime listing section that held their 2022 AGMs during the first half of this year, the percentage of those companies where at least one third of board members were independent reached 94 percent, compared to 79 percent in December 2021 and 63 percent in December 2020 based on the 1800+ companies currently listed on the Prime listing section. Although a one-third independent board is now the norm at Japanese companies, the same cannot be said for boards with higher independence levels. For Prime-listed companies that held their AGMs in the first half of 2022, only 23 percent had at least 50 percent board independence.

More Japanese companies are also adding female directors to their boards. The number of boards of Prime-listed companies that held their AGMs from January to June with at least one female director rose to 79 percent, which is a significant increase when compared with 67 percent as of December 2021 and 55 percent as of December 2020 for the full 1800+ Prime-listed company universe.

Source: ISS Board Data

In the past few years, it was already the norm for blue-chip companies to have at least a one-third independent board and a female director, and increases in board independence and female board representation have been continuous. However, these trends were further accelerated by the 2021 revision of Japan’s Corporate Governance Code and the TSE’s listing section reform which took effect on April 4, 2022.

In February 2020, the TSE announced its plan to reform its five listing sections (First, Second, Mothers, JASDAQ Standard and JASDAQ Growth) to three sections (Prime, Standard and Growth). With the reform, the TSE required former First section listed companies to have better corporate governance practices (and more liquidity) in order to be listed on the Prime section. The Standard section is for former First section listed companies that decided not to meet the stringent requirements, and also for companies previously listed on the Second and JASDAQ sections that wanted to upgrade their listings. The Growth section is mainly for former Mother section listed companies.

In June 2021, in sync with the TSE’s listing section reform, Japan’s Financial Service Agency revised the Corporate Governance Code, which requires higher corporate governance standards for companies listed on the Prime section. The revised Code calls for at least one-third independent board for all companies and majority independent board for controlled companies listed on the Prime section. On the other hand, the requirement for Standard and Growth sections remained status quo, with a requirement of only two independent directors for non-controlled companies and one-third independent board for controlled companies. In addition to the higher board independence standard, Prime section listed companies are required to disclose the impact of climate changes based on the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) framework, adopt majority independent advisory compensation and nomination committees, disclose some of their filings in English and use electronic voting system for institutional investors. The revised Code also calls for diversity – including gender, ethnicity and age diversity – at the board and workforce levels.

Although the Code is not a hard law and companies have the option to explain the reason for their non- compliance, most Japanese companies have traditionally chosen to comply. According to the Exchange, 88 percent of companies listed on the First section complied with more than 90 percent of the Code requirement as of 2020.

Despite the stringent requirements, more than 80 percent of former First section listed companies opted for the Prime section listing among which were many small- and mid-cap companies. While some companies chose the Prime section to keep their access to capital, others chose the Prime section primarily to keep their “top” listing status on the TSE. In the Japanese business community and the society at large, being on the First section is a “status” which makes it easier to access new businesses and recruit talented employees, especially in rural areas where many of small/mid cap companies operate.

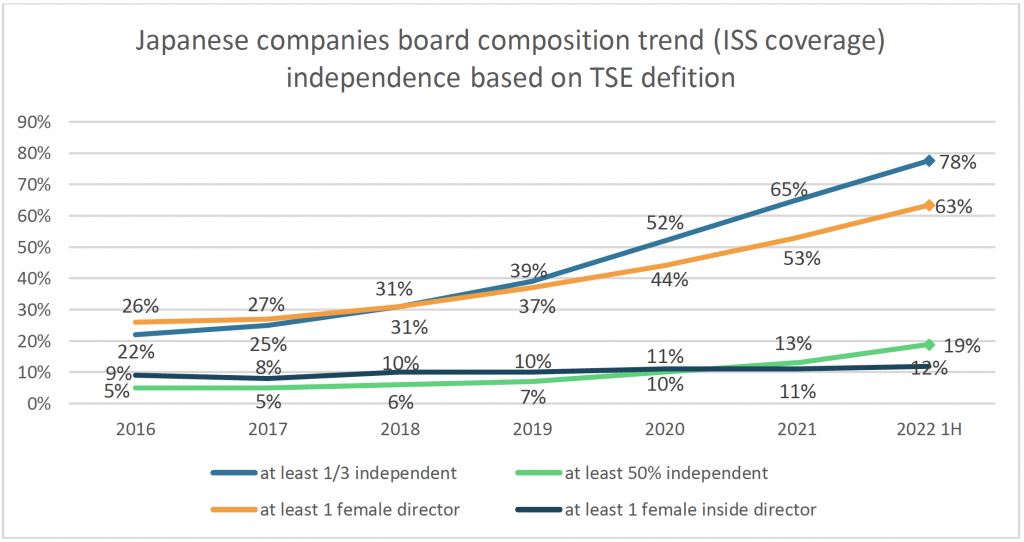

Because many small/mid companies opted for the Prime section, the reform has an impact on Japanese listed companies across all sizes. Based on all 2600+ companies under ISS coverage that held their AGMs in first half of 2022 (including small- and mid-sized companies in the non-Prime listing sections), the percentage of companies where at least one third of board members are independent (based on TSE definition) was 78 percent, and 63 percent of companies had at least one woman on their board.

Source: ISS Board Data

Following the Code revision and listing reform, many institutional investors updated their proxy voting policies this year, introducing stricter voting policies for outsider and female representation on boards. Many foreign institutional investors now have gender diversity policies for Japanese companies; and even among Japanese institutional investors, a number of large investors have either announced such policies this year or announced introduction for 2023 proxy season.

With one-third independent boards (based on TSE’s classification) now being the norm at Japanese companies, it may be reasonable to expect the small number of blue-chip companies failing the requirement such as Nintendo (30 percent independent board), Sumitomo Realty & Development (22 percent independent board), and Otsuka (30 percent independent board) to improve their board composition in the near future, as many of these companies could meet the requirement by appointing just one additional independent director.

With most companies now having at least one-third independent board (especially for companies listed in Prime listing section), whether institutional investors will further focus on board independence at Japanese companies (i.e. requiring majority independent boards), or shift their focus to other areas such as gender diversity, function of committees, and compensation, will remain to be seen.

On the gender diversity front, a number of blue-chip companies such as Shin-Etsu Chemical, Canon, Shimano, Sumitomo Realty & Development, and Toray Industries still maintain all male boards. It would be reasonable to expect such companies, especially blue-chip companies, to make improvements in this area. However, such improvement will likely come from the appointment of female outside directors and not female inside directors. Even at Prime-listing companies, the percentage of boards with female inside directors remain largely unchanged from 10 to 12 percent since 2018, and it is difficult to foresee a major shift in this area in the near future. Unlike outside directors who can be appointed from larger talent pools outside of the company, for Japanese companies to appoint female inside directors, companies first need to increase their in-house pool of talent from which inside director candidates can be drawn.

It has already been 36 years since the gender equal employment opportunity law prohibited discrimination in employment and promotion due to gender, which opened the door for women to work as executive candidates (or sogo-shoku). The first generation of those women would be in their late fifties, and theoretically should be fully qualified to be inside director candidates. However, many companies still argue that they do not have qualified candidates, which may be an indication of issues with equal employment and promotion at the workforce level. It will remain to be seen whether Japan will improve its gender diversity at the executive level in the next few years.

By: Taketoshi Yoshikawa, Japanese Custom Research, ISS Governance