This post is part of ISS ESG’s Thought Leadership Collection: 2023 Global Regulatory Update: Recent Developments and Key Themes in ESG-Related Regulations Globally. To access the full report, you can download it directly from the ISS ESG online library.

Introduction

Sustainability reporting has expanded dramatically over the past 20 years. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) reports that by the end of 2021, 316 sustainable-finance-dedicated policy measures and regulations existed across 35 economies, with sustainability disclosures accounting for almost 50% of recent policy measures and regulations. The sustainability reporting landscape took a major turn this year when, in June and July, respectively, two major standards-setters published their requirements weeks apart. In June, the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) published its own Sustainability Disclosure Standards in an effort to provide a global baseline for sustainability disclosures. A few weeks later, in July, the European Commission (EC or the Commission) published the final versions of the first set of sector-agnostic European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) under the new Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). These final ESRS are the culmination of initial drafts published by the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) in November 2022, with significant revisions made by the EC following public consultation in early July 2023. This chapter examines both standards, unpacks some of their differences and similarities, and analyzes how this will affect potential interoperability for those companies subject to both standards.

The International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) and the Global Baseline Goal

Following strong demand from international stakeholders for comparable, reliable, and granular disclosures, and in an attempt to consolidate the rapidly growing sustainability disclosures standards around the globe, the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation (IFRS) announced the creation of ISSB at COP26 in Glasgow in November 2021. ISSB became the product of the consolidation across the Value Reporting Foundation (VRF), the Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB), the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), and the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

IFRS S1 and IFRS S2: Repurposing TCFD

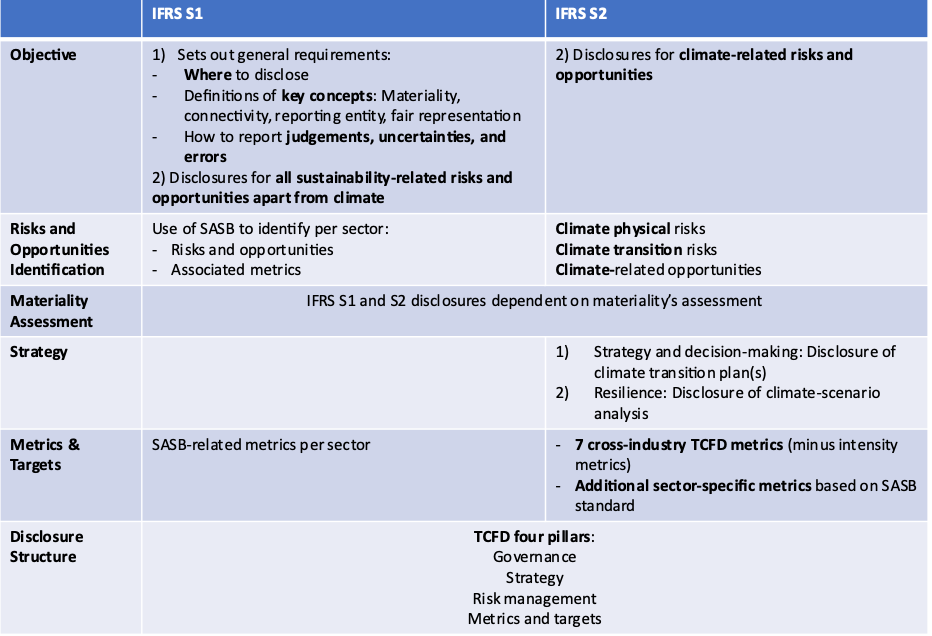

ISSB published, on June 26th, 2023, the first two Sustainability Disclosure Standards: IFRS S1 “General Requirements for Disclosure of Sustainability-related Financial Information” and IFRS S2 “Climate-related Disclosures.”

Both S1 and S2 draw heavily from TCFD’s four core pillars, which require entities to disclose details on Governance, Strategy, Risks Management, and defined Metrics and Targets. TCFD has been expanded to go beyond climate-related financial disclosures to include other sustainability-linked risks a company might be materially exposed to.

Materiality, Connectivity, and Sector-Specific Disclosures

IFRS S1, “General Requirements for Disclosure of Sustainability-related Financial Information,” sets out general requirements for the content and presentation of disclosures (materiality definition, connectivity with financial statements) but also requires an entity, in the absence of a specific Sustainability Disclosure standard, to disclose under IFRS S1 all sustainability-related risks and opportunities that could reasonably be considered material to the entity’s financial position and performance.

IFRS S2, “Climate-related Disclosures,” requires an entity to disclose information about its climate-related risks and opportunities that is useful to users of general-purpose financial reports in making decisions about providing resources to the entity.

Table 1: Disclosure under IFRS S1 and IFRS S2

Source: ISSB, ISS ESG

On materiality, ISSB clarified the concept and its assessment in its final standard. The clarification responded to feedback during the consultation period, to address stakeholders’ comments on the lack of clarity for terms such as “Enterprise Value” and “significant risks and opportunities.” Apart from this clarification, the standard maintained a focus on S1 and S2 disclosures’ relevance to materiality, particularly financial materiality, which is defined as “information about all sustainability-related risks and opportunities that could reasonably be expected to affect the entity’s cash flows, its access to finance or cost of capital over the short, medium or long term.” ISSB emphasizes that the disclosure standard is meant to provide information for primary users such as investors, lenders, and creditors.

IFRS S1 and S2 are required to be directly linked to financial statements, in an effort to increase connectivity between financial statements and sustainability-related risks and opportunities. TCFD’s key goal was always to provide better disclosures of the potential financial impact of climate-related disclosures. ISSB now is expanding this beyond climate keeping, true to the original TCFD goal of linking sustainability with financial statements, a goal which is potentially the most ambitious element of the standard. In this regard, ISSB recently consulted on their next agenda priorities; ISSB also proposed focusing their research on how to integrate further sustainability-related risks and opportunities with financial statements.

In its 2022 progress report the TCFD interviewed 42 investors, using companies’ climate-related disclosures, and reported that disclosure of actual and future financial impact is still not at the level expected. Companies would sometimes report climate-related data without including any financial statements on items such as capital deployed to support climate transition strategies or sales generated from low-carbon-related products and services. Those types of disclosures are still largely either unreported or lacking quality, which means reconciling the financial statements and corporate disclosures related to those items is a difficult task. What progress will be made under the new ISSB remains to be seen.

Both IFRS S1 and S2 require sector-specific disclosures, referencing SASB. IFRS S2 remains very much aligned with the TCFD recommendations, especially with the strategy pillar in which climate resilience and climate scenario analysis remain a requirement—a key element of the TCFD recommendations published in 2017. However, ISSB goes further in developing sector-based disclosures: where TCFD had created specific disclosures for only the financial sector, ISSB goes deeper and requires disclosure of targets and metrics beyond the seven original TCFD cross-industry metrics, including additional sectoral metrics based on the SASB standard, as well. Even though those disclosures are to be assessed against materiality and usefulness to primary users, it is clearly an important step forward, especially for the hard-to-abate sector and the level of granularity required for some of the additional SASB-related metrics.

The Promise of Enhanced Transparency

ISSB’s new standards have been largely welcomed by investors and other stakeholders as a significant move towards more transparency and global comparability when it comes to climate-related disclosures. Some elements, such as the inclusion of Scope 3, disclosures on Scope 3 categories, detailed disclosures on targets and progress, and additional sector-related metrics, reflect ISSB’s goal to go beyond the TCFD by bringing transparency and addressing some of the challenges the TCFD faced in the past.

ISSB’s announcement in 2022 of a Scope 3 package relief, allowing reporting entities to receive relief from Scope 3 disclosures against IFRS S2 in the first year of Scope 3 reporting, means that the first report that includes widespread Scope 3 emissions disclosures details will not be available before 2026. This relief also applies to the financial sector’s Scope 3, Category 15, emissions, which are related to investments. Such relief is a major difference from the TCFD recommendations.

Finally, importantly, the ISSB promise of a global baseline for investors, in which transparency and comparability of disclosures would be the foundation, is highly dependent on the adoption by different jurisdictions of the standards.

The European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) and a New Approach

In April 2021, the EC announced the adoption of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), in line with the commitment made under the European Green Deal. The CSRD replaces the existing Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) and substantially increases reporting requirements, in compliance with the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), for companies falling within its scope. Under CSRD, the EFRAG was appointed technical adviser to the Commission developing draft ESRS. EFRAG published the first draft ESRS in November 2022.

CSRD and ESRS: Great Expectations

The great expectations associated with CSRD rely on mitigating some of the NFRD shortcomings and expanding on the scope of companies covered by the new directive, as well as the specificity of the reporting requirements. NFRD can be thought of as the baseline for CSRD: both aim to establish greater transparency within the business sector, with CSRD ultimately adding more disclosure reporting than NFRD.

NFRD targets large public-interest companies: listed companies, banks, insurance companies, and other large entities with over 500 employees, representing approximately 11,600 companies. With the CSRD, EU policymakers expanded the scope of the NFRD to set a comprehensive standard for sustainability reporting in line with the goals of the EU Green Deal. The CSRD expands on the NFRD requirements, covering approximately 49,000 companies that are required to report under the new directive, expanding considerably the scope of mandatory sustainability reporting.

NFRD allowed reporting entities to choose among several possible reporting frameworks—local or international, generic or industry-/topic-based—for their nonfinancial information disclosures. EFRAG conducted an assessment in 2021 on the status of non-financial reporting in the context of NFRD and reported that many companies use more than three frameworks or standards, mostly global in scope, meaning no unified framework is applied. The greatest change CSRD introduces is the streamlining of these reporting requirements, in an effort to produce reliable and comparable disclosures. ESRS are composed of 12 standards: two cross-cutting standards (ESRS1 and ESRS2) and 10 topical standards covering sustainability across environmental, social, and governance matters.

In addition to the expanded breadth and depth of NFRD, CSRD and ESRS introduced new concepts such as the definition of double materiality, stakeholders, and mandatory external assurance.

The key concept which sets ESRS apart from other sustainability-related reporting standards is double materiality. ESRS focus on both financial materiality, by assessing the impact of sustainability-related risks and opportunities on future financial performance; and impact materiality, by assessing an entity’s impact on sustainability matters. Following final revisions in July 2023, all reporting companies are required to address General Disclosures in ESRS S2, but all other disclosure requirements are subject to a company’s materiality assessment. Further, if a reporting entity determines a disclosure requirement is not material, they must provide a “detailed explanation” to substantiate their materiality assessment.

The new rules aim to ensure that investors and other stakeholders have access to the information needed to assess investment impacts, risks, or opportunities arising from climate and other sustainability-related issues. To this end, and noting the double materiality perspective, ESRS 1 introduced definitions of two types of stakeholder groups whose interests would be catered to by ESRS implementation:

- Affected stakeholders: Those close to impact materiality

- Users of sustainability statements: Users of general-purpose financial reporting such as investors, lenders, and insurers

Finally, CSRD requires external assurance by an independent third-party assurance provider. Such assurance is expected to be initially limited and would be expanded to a reasonable (audit) assurance in the future.

Draft Changes, Phase-In, Added Complexity, and Delays

The Commission published for public comment a draft delegated act in early June 2023 that contained revised ESRS, finalizing the revised versions of ESRS a month later in July. While the overall structure did not change, there were significant changes compared to the November 2022 version prepared by EFRAG, which indicated a different approach by the European Commission to the prescriptiveness of CSRD.

Under the ESRS first draft, some sustainability matters and disclosure requirements were mandatory, regardless of the outcome of the materiality assessment. The EFRAG draft featured mandatory disclosures independent of any materiality assessment, including all climate-related disclosures in ESRS E1: Climate Change. These requirements implied all entities were subject to impacts, risks, and opportunities due to climate change. Under the final ESRS, however, the European Commission published changes that allowed all standards, with the exception of General Disclosures in ESRS 2, to be disclosed according to a materiality assessment.

Additionally, some disclosures are now voluntary under the final ESRS. Examples include the transition plan for biodiversity and ecosystems (ESRS E4) and information on non-employee workers in ESRS S1 (for example, information on adequate wages, social protection, and health and safety).

On top of those notable changes, the European Commission has introduced additional phase-in provisions, beyond those proposed by EFRAG. Multi-dimensional relief packages were published accompanying the new delegated act. These packages depend on company sizes, certain disclosure requirements, and sometimes both. They introduce a new level of complexity for entities and investors to grasp when reporting requirements are introduced. For investors, the relief packages also imply that it will take some time to access comparable granular disclosures and that a certain lack of uniformity across entities will remain in the near term.

For example, companies with fewer than 750 employees can delay scope 3 disclosures and own-workforce disclosures by one year and biodiversity by two years. All companies can delay by one year financial effects related to pollution, water, biodiversity, resource use, and datapoints on own workforce (social protection, persons with disabilities, work-related ill-health, and work-life balance).

ISSB and ESRS Interoperability: Commonalities and Key Differences

ISSB Adoption

The ISSB standard is fundamentally grounded in the TCFD recommendations, ultimately going further but with little major divergence. The ISSB assessment that entities reporting according to the TCFD recommendations should be fully prepared to report according to the ISSB standard suggests that countries that adopted TCFD-centric mandatory climate-related disclosures across their economies would likely be willing to adopt the ISSB standard.

In 2020, the U.K. government released a regulatory road map towards climate-related disclosures aligned with the TCFD recommendations. Meanwhile, the U.K. government indicated its intention to adopt the ISSB Standards for U.K. companies’ reporting, with an endorsement decision expected in the next 12 months.

However, the new ISSB standard’s success depends widely on adoption and therefore directly competes within the current and growing landscape of country-level/regional mandatory regulatory frameworks.

CSRD Impact Analysis on Companies in EU and Non-EU Regions

ISS ESG analyzed generally publicly available entity-level financial data, including data on public and a limited number of private entities, to understand the scale of CSRD’s impact on EU-based companies, as well as other companies outside the EU. (The CSRD’s scope impacts large non-EU entities.) Hence, this analysis does not represent the complete universe impacted by CSRD implementation. The regulation defined various eligibility criteria for entities, as stated below.

ISS ESG analysis found approximately 6,800 companies subject to CSRD regulation, of which about 5,000 companies are from the EU and about 1,800 would be considered non-EU. The 6,800 companies are only a fraction of the 49,000 companies potentially impacted; by extrapolation, this could mean approximately 13,000 non-EU companies would be subject to both CSRD and ISSB standards. This highlights the importance of interoperability between the two standards.

The Impact of Standards Alignment

During their respective consultation periods, both standards received significant feedback regarding their interoperability. This feedback led to revisions in both standards that may have contributed to greater harmonization.

The ISSB standard made room for different regional contexts, directly quoting ESRS, to remain policy agnostic. This resulted in some cases in differing disclosure requirements, such as strategy and climate resilience disclosures. Also, to encourage adoption and to reduce the reporting burden on companies, the ISSB standard provided relief packages, where companies in their first year of reporting do not need to report on Scope 3 emissions disclosures. These amendments reflect a change from the original ambitions of the TCFD.

The changes published by the European Commission within the new delegated act also show a reduction in ESRS requirement ambitions. To better align with ISSB S2 on the materiality assessment, the European Commission changed ESRS E1 on climate change to be subject to materiality assessment rather than being mandatory, as initially proposed by EFRAG in November.

Key differences between ESRS and ISSB standards stand out on issues related to materiality, the depth of topics covered, and the comprehensiveness of reporting requirements. For companies looking to engage with the European market, extensive reporting and large operational changes would be required to meet the ESRS standard. In contrast, the ISSB standards consider the importance of “reasonable and supportable information that is available to the entity at the reporting date without undue cost or effort.”

Conclusion

The degree of interoperability between the ISSB and ESRS disclosure standards remains an open question, for now. Key elements, such as the TCFD-structure approach for both standards and the higher level of requirements for the regional standard ESRS versus the international standard, suggest a certain degree of interoperability between the two standards. Nevertheless, differences on concepts such as materiality definitions, the standards’ flexibility on entities’ application of materiality assessments, and different relief packages within the standards could considerably reduce the level of inter- and intra-standard comparability across reporting companies.

Still, given the amount of new information expected to be reported against both standards, the ISSB SASB-based sectoral metrics and the depth of ESRS metrics will provide disclosures investors could find useful, regardless of the standards’ comparability.

Explore ISS ESG solutions mentioned in this report:

- Financial market participants across the world face increasing transparency and disclosure requirements regarding their investments and investment decision-making processes. Let the deep and long-standing expertise of the ISS ESG Regulatory Solutions team help you navigate the complexities of global ESG regulations.

- Identify ESG risks and seize investment opportunities with the ISS ESG Corporate Rating.

- Assess companies’ adherence to international norms on human rights, labor standards, environmental protection and anti-corruption using ISS ESG Norm-Based Research.

By: Candice Coppere, Climate Analytics Head, ISS ESG

Sam Schrager, U.S. Climate Analytics Lead, ISS ESG

Mohammad Zeeshan, Analyst, Climate Research, ISS ESG