Tax avoidance is an issue as old as taxation itself. Multinational tax avoidance, however, including through the use of tax havens, has achieved prominence primarily in the 20th century. While the types of financial mechanisms used to shift profits and avoid taxation have changed, the motivations of corporations and the impact on societies are unchanged. Corporations seek to minimise their tax burden to increase their profits, and when they do, less money is available for essential public services such as healthcare, education, defence, or roads and public transport.

The Tax Justice network estimates that AUD $624 billion in tax revenue is lost every year to tax havens, with a total of between AUD $30 trillion and AUD $47 trillion in financial assets residing in those jurisdictions. If the amount of money lost to tax havens could be redirected it would cover between a ¼ and a ⅓ of the cost of addressing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in low- and middle-income countries.

It’s Not Just About Values

In addition to presenting a challenge to investors seeking to have a positive impact in the world, tax avoidance raises reputational and compliance related risks. A recent example of the potential magnitude of compliance risks can be seen in the size of the settlement agreement between Rio Tinto and the Australian Tax Office (ATO) in July 2022, stemming from the company’s alleged use of profit-shifting arrangements. Through its Tax Avoidance Taskforce, the ATO investigated Rio Tinto’s use of Singapore based subsidiaries to reduce its Australian tax burden, resulting in an eventual settlement amount of AUD $613 million.

Despite its large size, the settlement with Rio Tinto represented a very small proportion of the company’s net profits in 2021, demonstrating the difficulty faced by regulators when prosecuting companies of this size for tax avoidance. Furthermore, even for regulators, tax avoidance is notoriously difficult to detect. One of the reasons that detection is difficult is that it can occur in jurisdictions with standard corporate tax rates, as well as in tax havens. In any location, companies may structure their finances in such a way as to avoid taxation, or take advantage of bespoke tax regimes/rulings in the jurisdiction which may not be available to their competitors.

Complications for Investors

One of the chief hurdles that investors face when seeking to address the issue of tax avoidance, especially in the case of tax havens, is that of definition. There are many ways that tax havens have been defined and measured, but generally, tax havens are understood to be “economies with no or low rates of tax that lack transparency and do not share information with other jurisdictions”. Also called offshore financial centres (OFC’s), some academics differentiate between tax havens which are primarily “sinks”, and those which are primarily “conduits” of capital.

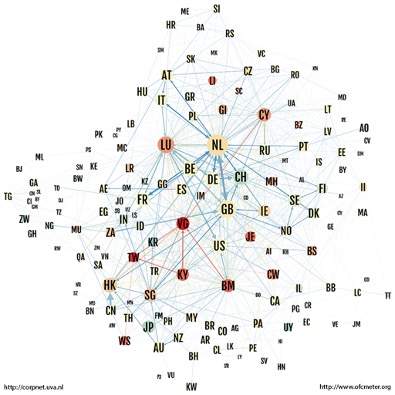

Figure 1: Sinks vs Conduits

Source: CORPNET’s OFC Meter, presenting networks of relationships between Sink-OFC’s and Conduit-OFC’s and other jurisdictions. Darker colours are indicative of the size of the value which flows through or into those jurisdictions which cannot be explained by economic size.

According to research conducted by CORPNET Research Group at the University of Amsterdam, “sinks” are jurisdictions in which a disproportionate amount of value disappears from the economic system, while “conduits” are the jurisdictions through which that value moves before arriving at “sinks.” In 2017 the research group identified 5 conduits of capital: the Netherlands; the United Kingdom; Switzerland; Singapore; and Ireland. Jurisdictions defined as sinks include: the British Virgin Islands; the Cayman Islands; and Bermuda.

These three jurisdictions also top the Corporate Tax Haven Index published by the Tax Justice Network, which ranks those countries which are the greatest enablers of corporate tax avoidance. Notably, all three of these jurisdictions are British Overseas Territories, and, also in the top 20 entries on the list are three British Crown Dependencies: Jersey; Guernsey; and the Isle of Man. According to the 2021 Corporate Tax Haven Index, these six territories and crown dependencies, where the British Queen is still the head of state, account for over 26% of the world’s corporate tax avoidance. The fact that these jurisdictions are territories and crown dependencies rather than countries complicates matters for investors seeking to identify corporate use of tax havens for the purpose of tax avoidance – there is no requirement for companies to report their presence in these locations.

Testing an Approach for Tax Havens

One of the purposes of this paper is to test an approach that could be used by investors to examine the corporate use of tax havens – using Australian companies as an example. In doing so, the authors make a number of adjustments to commonly published lists of tax havens:

- As the list by CORPNET is several years old, it was cross referenced with the more recent Tax Justice Network list, and only countries appearing on both lists are considered.

- As there is no requirement for companies to report their presence in jurisdictions which are not countries, these jurisdictions (primarily crown dependencies and British Overseas Territories) have been excluded from the list of tax havens being considered.

- As countries which serve as conduits may be used for other legitimate corporate interests, these were also excluded, with the addition of Hong Kong, which, while operating as a sink for countries in Europe, functions more as a conduit for Australian based firms seeking to do business in China.

Of the 13 countries and economies which resulted from this process, 43 companies in the ASX300 had a subsidiary incorporated in at least one of them. The three jurisdictions with the highest level of ASX300 participation were:

- Taiwan (12 companies)

- Mauritius (10 companies)

- Luxembourg (21 companies)

Of the three jurisdiction listed, Luxembourg is notable, in that it has faced significant criticism of its tax structures in the last decade. In 2014, the LuxLeaks exposed the types of tax structures used in Luxembourg which allowed companies to achieve an extremely low level of taxation, if they were taxed at all. In addition, the International Monetary Fund has reported that Luxembourg, with its small population of 600,000, received foreign investments which equate to AUD $9.6 million AUD per person. As the average salary in Luxembourg in 2020 was $96,000 AUD, this figure raises legitimate questions for international taxation bodies. Finally, as noted by the European Commission in a 2020 Country Report on Luxembourg:

“Economic evidence suggests that Luxembourg’s tax rules are used by companies that engage in aggressive tax planning”.

The 21 companies in the ASX that had at least one subsidiary in Luxembourg were primarily clustered in the following sectors:

- Financials (7)

- Real Estate (6)

- Information Technology (3)

- Materials (3)

Each of these companies may have legitimate business interests for their operations in such jurisdictions. Companies in this position could consider providing detailed disclosure around their reasons in such cases, to minimise the risk of perceptions arising that their presence is due to comparative tax advantages. For the 43 companies identified in the process above, ISS ESG has found that only 4 companies publicly disclose such a statement.

Clients interested in this topic can access relevant data through the ISS ESG Corporate Rating, through relevant Norm-Based Research, and through the ISS ESG Country Rating’s Financial Secrecy Indicator, which evaluates a country’s exposure to financial secrecy, tax evasion and illicit financial flows (such as money laundering). It takes into account a jurisdiction’s laws, rulings and international treaties to assess how secretive its policies are, and the scale of financial activities attracted by this secrecy as measured by the Financial Secrecy Index of the Tax Justice Network.

What Does the Future Hold?

In July 2021, 130 countries and jurisdictions, representing more than 90% of global GDP, joined a new two-pillar plan by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to reform international taxation rules. The plan seeks to do this by compelling companies to pay a fair share of taxation in the countries in which revenue was generated, and establishing an effective global minimum tax of 15% on multinational companies. The OECD estimates that this will generate over AUD $210 billion per year in new tax revenue.

While some of the finer details have yet to be determined, various governments have begun to update their regulatory guidelines to better reflect this plan. For example, in the USA, the Biden administration attempted to implement a 15% effective minimum tax rate, but political opposition threatens to reduce its effectiveness. In Australia, the Treasury Department of the Federal government has recently concluded the consultation period for a Multinational Tax Integrity and Tax Transparency consultation paper, which will support the Federal government’s election commitment to address issues associated with multinational taxation. The department also clearly identifies the OECD plan as being of central importance to the Government’s approach.

While there is progress in this space, there will always be companies which seek to use tax-minimizing architectures to their advantage. Responsible investors have an opportunity to act on issues of tax fairness and transparency, not just because of the potential investment risks associated with corporate tax liabilities, but also in order to maximize their potential positive impact in the world and contribute to the realization of the UN-backed Sustainable Development Goals. This can be achieved through investors actively mitigating risks by incorporating metrics and data on tax responsibility into their investment decisions, and actively engaging with businesses on transparency and fairness in taxation.

Explore ISS ESG solutions mentioned in this report:

- Identify ESG risks and seize investment opportunities with the ISS ESG Corporate Rating.

- Assess companies’ adherence to international norms on human rights, labor standards, environmental protection and anti-corruption using ISS ESG Norm-Based Research.

- Access to global data on country-level ESG performance is a key element both in the management of fixed income portfolios and in understanding risks for equity investors with exposure to emerging markets. Extend your ESG intelligence using the ISS ESG Country Rating and ISS ESG Country Controversy Assessments.

By: Daniel Parris, Research Analyst, ISS ESG