October 10 is World Mental Health Day, a day that aims to raise awareness about mental health issues. Since the day was first recognised in 1992 there has been an increasing recognition of the significance of mental health and its impact on wellbeing. But while much progress has been made, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought the inadequacies of our current approach into stark relief. As investors become increasingly interested in the environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance of the companies they own, and aware of the potential financial materiality of topics such as mental health, more attention will need to be devoted to understanding and addressing this issue.

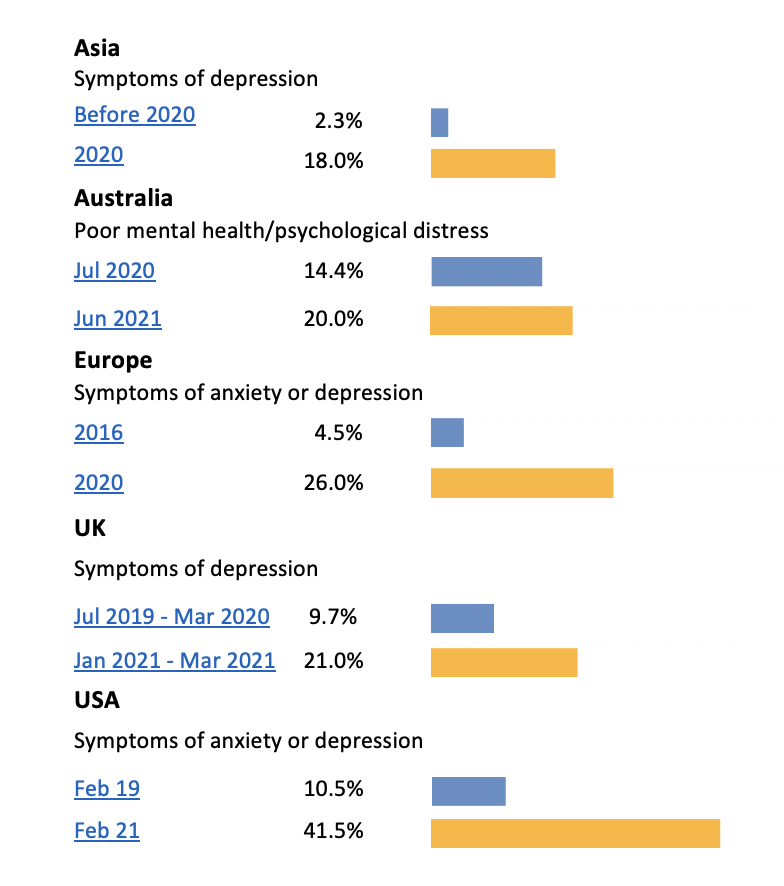

The mental health concerns associated with the pandemic are relatively well known. Lockdowns and social distancing have proven to be reasonably effective at limiting the spread of the disease and the potentially life-threatening respiratory symptoms associated with it, but have also been shown to lead to psychological distress within the general population (See Figure 1). As one recent journal article put it, “mental health concerns should not be viewed only as a delayed consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, but also as a concurrent epidemic”.

Figure 1: Proportion of the population with mental health concerns before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

| Asia Symptoms of depression | Before 2020 2020 | 2.3% 18.0% |

| Australia Poor mental health/psychological distress | Jul 2020 Jun 2021 | 14.4% 20.0% |

| Europe Symptoms of anxiety or depression | 2016 2020 | 4.5% 26.0% |

| Europe Symptoms of anxiety or depression | 2016 2020 | 4.5% 26.0% |

| UK Symptoms of depression | Jul 2019 – Mar 2020 Jan 2021 – Mar 2021 | 9.7% 21.0% |

| USA Symptoms of anxiety or depression | Feb19 Feb21 | 10.5% 41.5% |

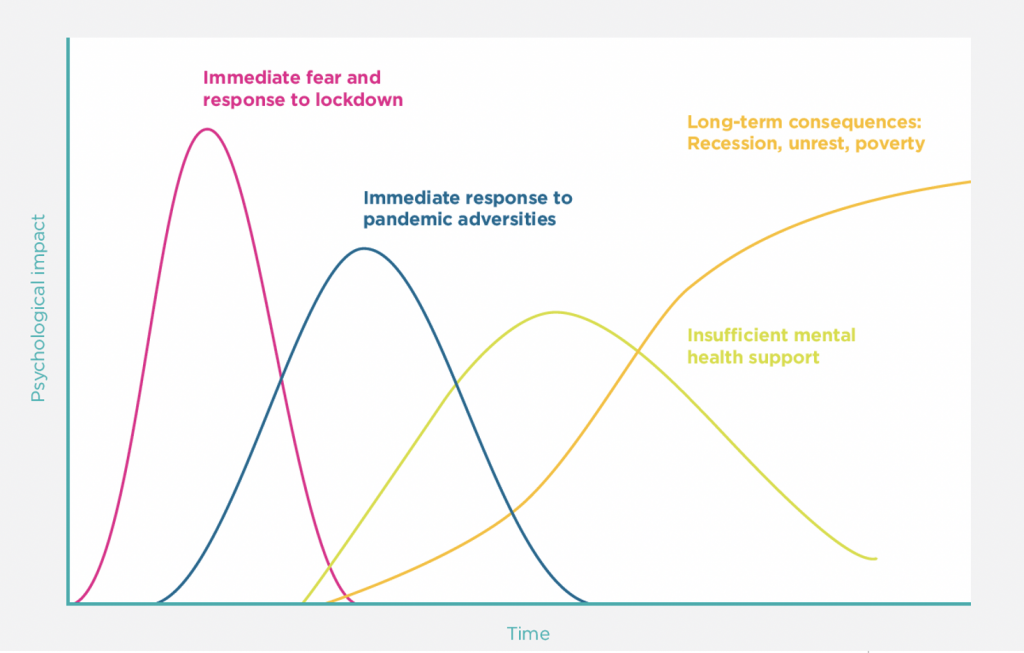

The COVID-19 pandemic has not affected all people equally. Those with underlying health issues, young people, elderly people, mothers, low-income households, and those living alone, have all been particularly exposed to mental health risks. For example, US researchers found that over half of women with school-aged children said that the pandemic had affected their mental health, with one in five reporting that this effect had been ‘major’. Young people have also been at risk, in part because they experience higher employment and income insecurity. In Australia, almost one in three (30%) younger Australians (aged 18 to 34 years) experienced high or very high levels of psychological distress in June 2021, compared with less than 18% of people aged 35 or older. And there is a range of secondary effects, with new or increased substance use and increased suicidal ideation, particularly in young people. And the impacts may last long after the pandemic has ended, with research estimating that some mental health impacts will be still be felt in 2029.

Figure 2: A timeline of the mental health impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic (World Happiness Report 2021)

The pandemic has also exacerbated disparities in access to health care that existed before the pandemic. For example, “between 76% and 85% of people with mental health conditions receive no treatment for their condition” in low- and middle-income countries. Where mental health services did exist before the pandemic, hospital capacity has sometimes been diverted to service critical COVID-19 patients. In other places, mental health services have been shut down or remain out of reach due to access and affordability, as can be seen in the United States and across Europe (particularly Eastern Europe). While governments across the world have increased their focus on mental health and shifted, where possible, to online delivery, more action is needed.

In the context of the workplace, these types of risks can be referred to as psychosocial risks, which the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA) defines as risks to workers’ psychological or physical wellbeing that “arise from poor work design, organisation and management, as well as a poor social context of work”. Some industries and occupations, such as small business owners and essential or frontline workers, have been particularly vulnerable to psychosocial risks. For example, during the pandemic, 50% of healthcare workers in China have reported high rates of depression, while 47% of healthcare workers in Canada report a need for psychological support. Even for those workers who are not considered ‘essential’ or ‘front line’, many have had to shift to remote work environments which can also exacerbate psychosocial risks, and make issues harder to detect by employers.

“Have you ever noticed how we seem to engage differently when comforting someone with a physical illness than we do someone fighting a mental illness? We’d never try to “fix” a loved one who is fighting a physical illness, yet with mental illness, too many of us feel that by offering a few “helpful” suggestions we can make the mental illness go away. I pose this as I myself fell into such a trap, later learning that such a clearly misguided belief (however well intended) is fraught with stigmatic beliefs around mental health, beliefs which aren’t present when discussing physical illness. If outdated and ill-informed stigmatic beliefs do affect how we misconnect, therefore it would be plausible that by unlearning such stigmatic beliefs WE all can have a positive and more empathetic influence towards loved ones who may be struggling with mental health.”

Rob Prugue is the Founder and Chairperson of People Reaching Out to People, or PROP for short. Launched in November 2016, PROP’s mission is to utlize recent and well documented findings around mental health to aid in the collective unlearning of the stigmatic beliefs many of us subconsciously embrace on this issue. With the help from mental health practitioners, PROP has compiled a four part tutorial whose sole purpose is to unlearn our subconscious stigmatic beliefs around mental health.

“Looking at life post Covid, we believe that the next frontier within mental health awareness will be conducted via the workplace. The challenge will be offering access to mental health support to those who may fear that their mental health issues may limit their career growth and compensation. Recent surveys have shown that employees are already placing work/life balance and mental health ahead of career advancement. Overcoming fears of staff in coming forward will be a vital factor in strengthening job loyalty, and therefore be better for both employer and employee.

In conjunction with work done internally to de-stigmatise mental health, let alone finding independent access to mental health support, employers should and can work with employees to create a healthy work environment. While the pandemic will one day end, mental health ramifications will carry on indefinitely. Employers who lag in creating such environment will suffer as staff retention will be challenged as employees seek a better work environment.”

Many companies are concerned about this ‘concurrent epidemic’, and for good reason. The costs to businesses and society are staggering, with the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimating that the global economic cost is $1 trillion per year in lost productivity. Spending on mental health insurance claims is often substantially higher than for other work-related injuries, and time off for psychological injuries is often greater as well. In the Life Insurance industry, life insurance companies have developed different approaches to promote healthy living to members, covering both good physical health and mental wellbeing. The focus is not just about living longer, but also on health solutions that focus on customers as individuals, taking into account mental, physical, social and financial health. An example of this is offering customers and staff confidential access to a network of mental health professionals, something that is recognised in the ISS Market Intelligence Plan for Life Health & Wellness Insurance Awards program.

In Australia between 2010-11 and 2014-15, “typical compensation payment per claim was $24,500 compared to $9,000 for all claims”, and “typical time off work was 15.3 weeks compared to 5.5 weeks for all claims”. And in the United States employers spend “on average, over $15,000 a year on employees who experience mental distress”, and insurance claims are “on average, up to four times higher per annum than for claims relating to physical injuries”. In addition to lost productivity and higher costs for employers, psychosocial risks can lead to employee disengagement, absenteeism, and high staff turnover as employees seek more supportive environments.

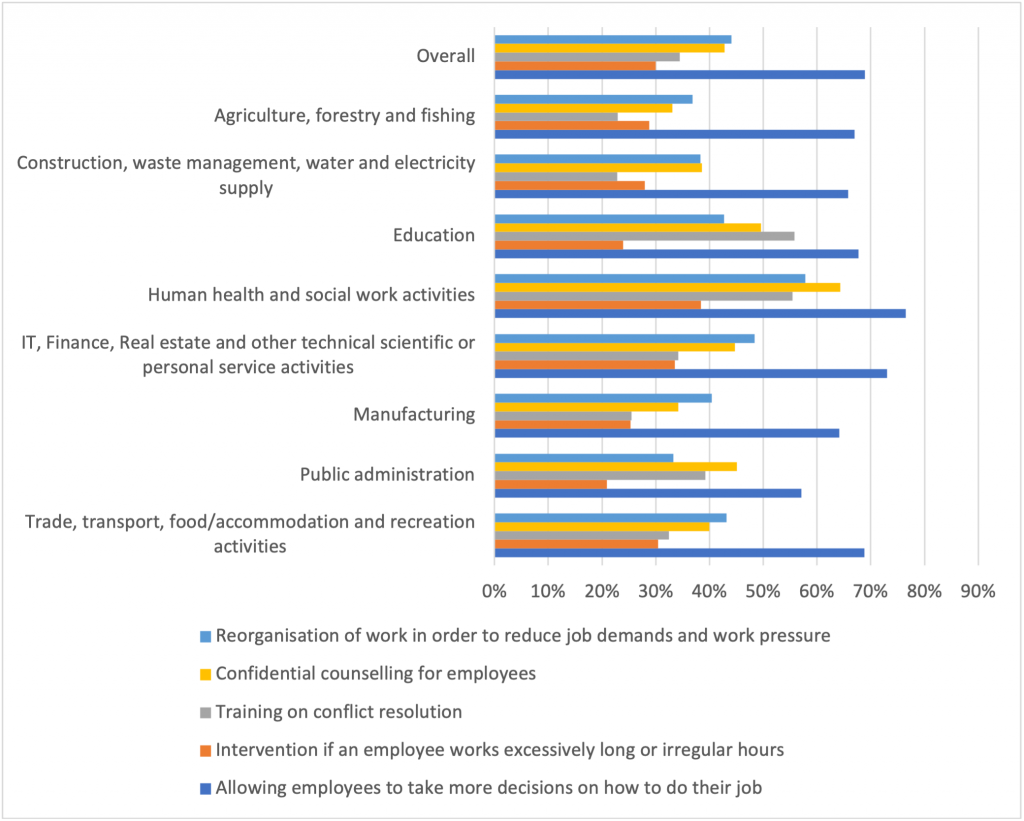

Many industries are only just beginning to implement measures to address psychosocial risks (see, for instance, Figure 3). ISS ESG, which also considers psychosocial risks in its Corporate Ratings (where relevant), has found that company performance is often inadequate. For instance, companies in the finance industry were typically rated as ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’ on the issue of mental health management, and most companies prioritise therapeutic approaches rather than prevention.

Figure 3: Measures to prevent psychosocial risks in the last three years (EU-OSHA 2019)

If companies are to reduce their exposure to psychosocial risks, a combination of preventative and therapeutic approaches are needed. That is, companies should seek to prevent, as much as possible, the psychosocial stressors present in the work environment, and support employees as they recover from psychological concerns. Research by, for example, EU-OSHA (here and here), Safe Work Australia, and Worksafe Victoria, has identified measures to address psychosocial risks. Prevention can be achieved by:

- Identifying and assessing existing hazards (i.e. through audits/risk assessments);

- Implementing prevention measures, which may include:

- Elimination of the hazard where possible (i.e. changing job design);

- Creating distance between the employee and the hazard (i.e. role or team reassignment); and

- Minimizing exposure to the hazard (i.e. mental health awareness and training, providing clarity about role expectations and employee effort and reward); and

- Ensuring that psychosocial risks are sufficiently monitored so that early intervention can occur.

Where an individual has been affected by a psychosocial stressor, measures to alleviate mental health problems could include:

- Psychological support (i.e. employee assistance programs);

- Workload adaptation; and

- Return-to-work/rehabilitation programs.

When implemented, these measures can significantly reduce a company’s exposure to psychosocial risks, enhance employees’ wellbeing, and have a positive impact on business productivity.

While awareness days such as “World Mental Health Day” are useful reminders, awareness is not enough. We know that treatment for depression and anxiety works, with the WHO finding that every $1 invested in scaling up treatment leads to a return of $4 in better health and ability to work. And we know that companies have an important role to play. Not only do they have a duty to investors to ensure that they effectively manage financial risk, but they also owe a duty of care to their employees, as well as grappling with the impact they have on the broader world. As owners of these companies, investors and investment managers should ensure that psychosocial risks are properly managed by the companies within their portfolios, even after this pandemic has ended.

Explore ISS ESG solutions mentioned in this report:

- Identify ESG risks and seize investment opportunities with the ISS ESG Corporate Rating.

By Daniel Parris, Research Analyst, ISS ESG