“Humanity’s 21st century challenge is to meet the needs of all within the means of the planet.” (Raworth, 2017)

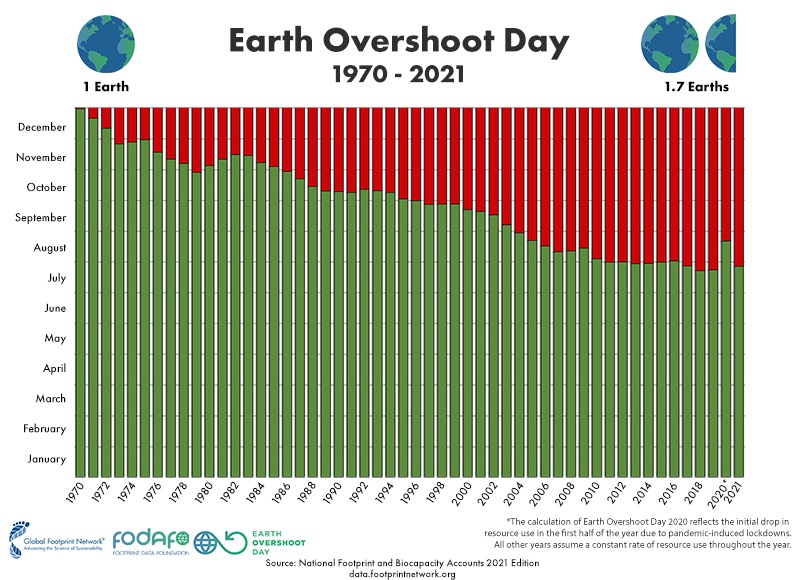

Each year the Global Footprint Network measures humanity’s overall global ecological footprint and estimates the day on which demand for natural resources surpasses the amount the planet can regenerate within the same year. In 2021, the so-called Earth Overshoot Day was July 29. In other words, collectively we have consumed more than the earth can regenerate within a year – 1.7 earths would be necessary to meet humanity’s resource demand this year. In light of a growing global population, the demand for natural resources is only expected to increase.

Figure 1 The Development of Humanity’s Resource Use since 1970

Our current economic system can be described as linear. We extract resources, turn them into products, we use them, and then we dispose of the product and its components as waste. This model leads to the loss of economic value through the wastage of resources and energy, as well as being behind the earth’s most pressing ecological challenges such as climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution.

One of the solutions for tackling these challenges is the concept of a circular economy. ISS ESG analysis references the definition of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF) (the most recognized independent knowledge hub for circular economy): “A circular economy is an industrial system that is restorative or regenerative by intention and design”. Such an economic model would be able to endlessly circulate materials and nutrients that are safe for the environment and humanity.

The circular economy is distinct from the concept of recycling and goes beyond the three R-framework of Reduce, Reuse and Recycle. Recycling generally refers to “downcycling”, which describes the process in which a product’s material decreases in value or quality. An example of downcycling is when PET bottles are melted into a park bench at the end of their life cycle. Experts note that to be truly circular, economic systems should strive for “upcycling”, meaning that recycled product components maintain or enhance their value. An example would be using car components in another car instead of sending them to a scrapyard that downcycles the steel for building material.

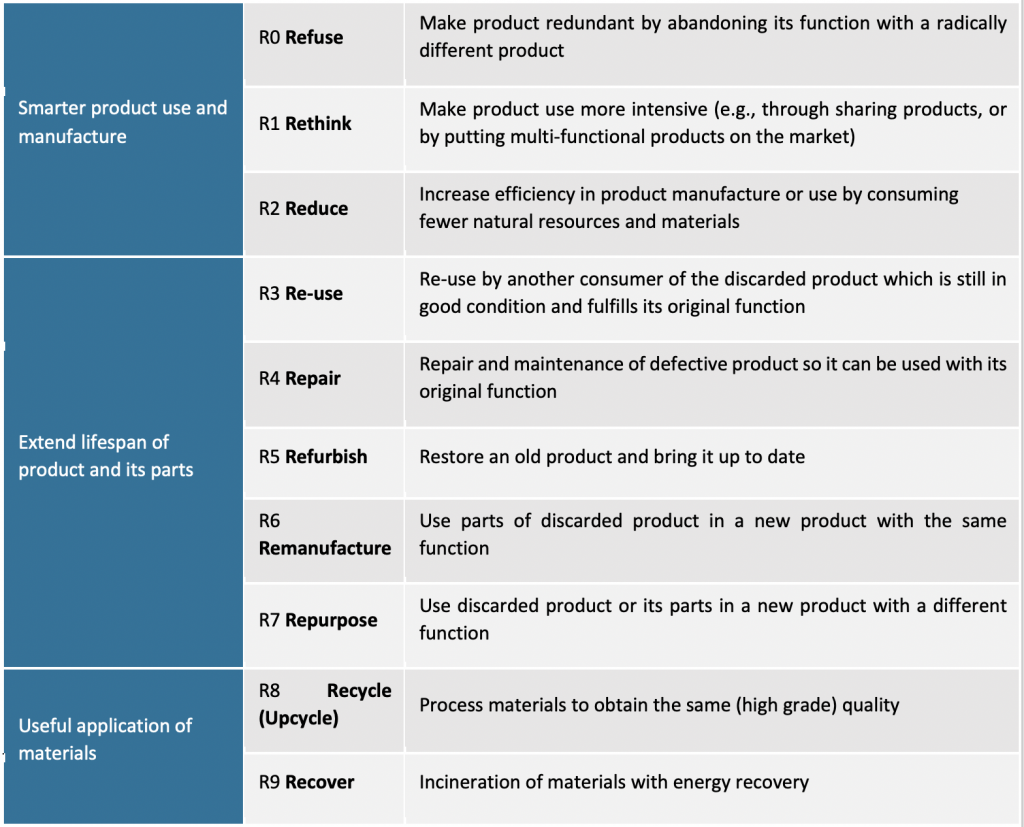

Circular strategies can be described according to the 9-R concept in the figure below. In particular, the “Refuse” strategy refers to refraining from using harmful chemicals. This strategy ensures the health and safety of the environment, consumers, and workers along the supply chain. It also facilitates the upcycling of components into a similar or other product of higher quality, and is ideally considered in the design phase of product development. The importance of chemicals in a circular economy is supported by the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), and is also a key element of the Cradle to Cradle standard for product certification (the most comprehensive certification for circular products).

Figure 2: Circular Activities along the product lifecycle, in order of priority (Slightly adapted from Potting et al., 2017, P. 5)

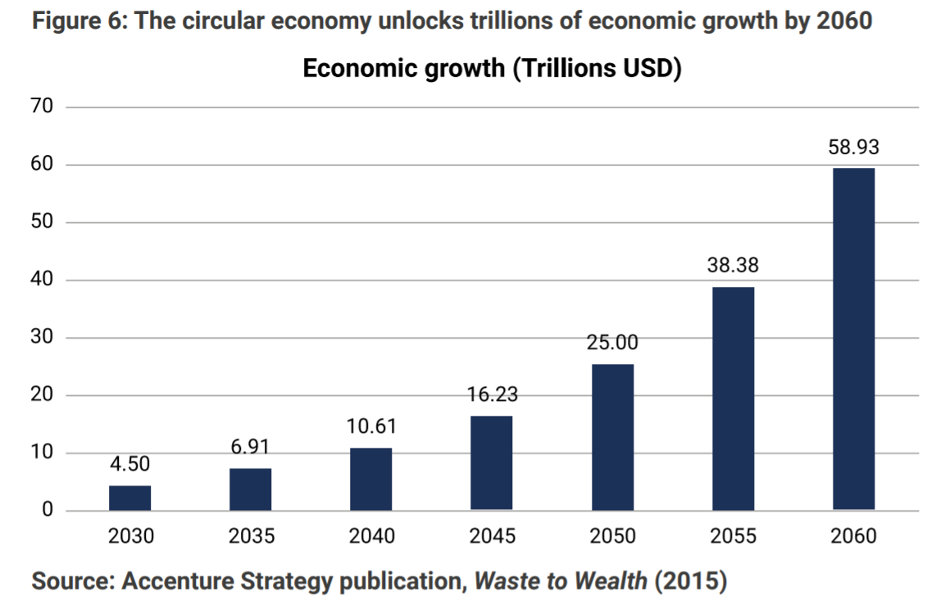

From an economic perspective, the circular economy is estimated to constitute a “multi-trillion-dollar (…) opportunity”. Accenture’s estimate for the European market concludes that the “circular economy could generate USD 4.5 trillion of additional economic output by 2030 on an annual basis”.

Figure 3: The circular economy’s expected economic growth in Europe

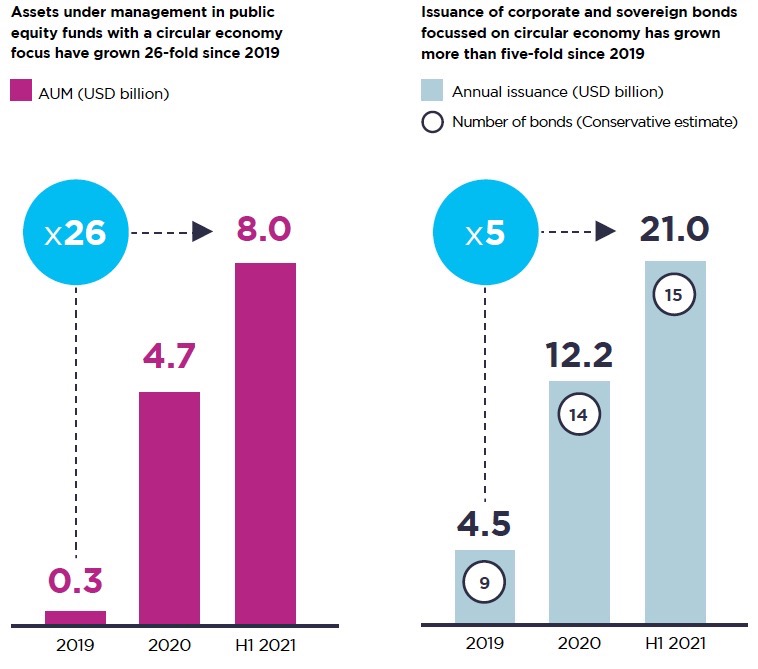

The financial market has started picking up on the topic as well. The number of circular economy-themed public equity and private market funds, and bond issuances, has been increasing during the last couple of years. One of the most prominent examples is BlackRock’s Circular Economy Fund. Launched in 2019 with $20 million, the fund now has a market capitalization of in excess of $2.3 billion.

Figure 4: The increasing trend of public equity funds and bonds in the last two years

The United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) calls for the integration of the circular economy into the environmental, social and governance (ESG) evaluation of corporations and thus, ultimately into the investment decision making process. The adoption of circular economy strategies has the potential to mitigate the earth’s most pressing environmental challenges. The EMF points to the concept’s importance in delivering on two topics currently front and center for the finance industry: Climate Change and ESG. Figure 5 below illustrates that 45% of global greenhouse gas emissions can be tackled by rethinking and redesigning our products as well as how food is grown, while the rest (55%) could be addressed by energy efficiency gains and switching to renewable energy sources.

Figure 5: The importance of a circular economy in addressing climate change

In addition to climate change, the circular economy can contribute to the realization of the UN Sustainable Development Goals by positively impacting air and water quality, biodiversity, and soil.

| Case Study One example reflecting these positive impacts can be found in this case study by Cradle to Cradle: A textile company produced a garment without any toxic chemicals. The company refrained from using around 8000 chemicals that are usually part of the production process. Consequently, employees were no longer required to wear protective equipment against the harmful substances, fabric remnants could be used as mulch, and the wastewater was as clean as potable water. Besides these apparent social and environmental advantages, adopting circular practices also included economic benefits for the company. The results included a decrease in production costs. |

As the EMF describes it: “Driving such an industrial transformation, the circular economy boosts innovation, creates business opportunities, and enhances resilience, providing a strong economic rationale that goes beyond ESG”.

Earlier this year, ISS EVA evaluated the financial materiality of the circular economy. The analysis concluded that in aggregate circular economy-related companies are returning above their cost of capital, creating true economic profit. The firms tend to be relatively expensive, however, so investors need to be cautious when assessing the level of Risk-adjusted Profitability and Valuation. Further research by the EMF, in collaboration with Bocconi University and Intesa Sanpaolo, has had a closer look into the causal relationship between circular economy, investment risk, and returns. The analysis finds that “the more circular a company is, the lower its risk of default on debt over both a one-year and five-year time horizon.” Therefore, financing corporations that are in the process of moving towards a circular economy can have a de-risking investment effect. In addition, “higher levels of circularity are driving superior risk-adjusted stock performance for European listed companies”. This indicates a positive effect of circular economy strategies on investment performance and on the default risk for financed enterprises.

Given regulatory developments such as the EU Green Deal’s Circular Economy Action Plan and the EU Taxonomy, the circular economy is increasingly being promoted in Europe. France, for instance, passed a circular economy law in 2021. Other countries such as China and Chile have also presented circular economy plans. The pressure on private actors is expected to increase and regulatory drivers may affect investors, which is another reason to stay ahead of the game and leverage circular economy investment opportunities.

ISS ESG has recently established a dedicated circular economy team with members from different departments and is looking forward to providing expertise and tools to assist in identifying new investment opportunities. We will be expanding on the topic over the next few months: Stay tuned!

Explore ISS ESG solutions mentioned in this report:

- Identify ESG risks and seize investment opportunities with the ISS ESG Corporate Rating.

- Understand the F in ESGF using the ISS EVA solution.

By Hanna Taya, Analyst, ISS ESG Yuka Manabe, Senior Associate, ISS ESG