According to an assessment by the United Nations Children’s Fund, half of the world’s population could be living in regions experiencing water scarcity by 2025. Already four billion people—almost two-thirds of everyone on earth—experience severe water scarcity for at least one month of the year. Because many of the most critically water-stressed states are also the least economically developed, water scarcity complicates the goal of ensuring that development is safe and responsibly managed.

The challenges associated with water insecurity and development have implications for investment in the global economy. Development Banks may contribute to both the problems of water scarcity and possible solutions. Investors interested in these Banks’ approach to water and development issues can draw on the ISS ESG Corporate Rating.

The Problem of Water Scarcity

Water is essential to all life and most activities on Earth. While water supplies are self-renewing, they are not infinite. According to the FAO, 70 percent of the freshwater withdrawn for human use is directed at irrigation for food production, and 40 percent of our food supply relies upon such irrigation. As the effects of climate change are felt increasingly acutely and reliance on irrigation to supplement decreasing rainfall grows, these proportions are expected to rise.

When stressed and finite resources are redistributed, typically some gain access and others lose it, and a pressing problem for development emerges. For instance, diverting water from farmland to cities reduces water available for crop cultivation and ultimately reduces income for inhabitants of rural areas. By contrast, diverting water to agriculture reduces the amount of water available to urban inhabitants and exacerbates existing or looming water shortages in urban areas.

Possible consequences of overreliance on these kinds of human interventions include disrupting adequate water supply to densely populated urban areas; disrupting the water supply to crops, thereby affecting food supplies; and even conflict related to distribution.

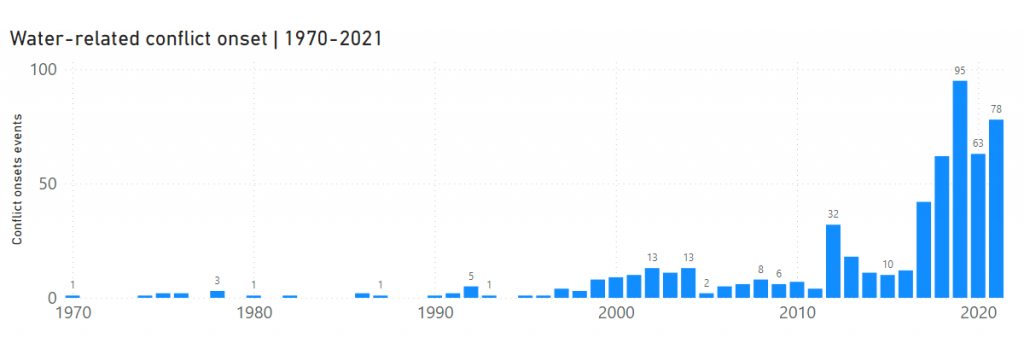

The Water Conflict Chronology, a project of the Pacific Institute that compiles information on water-related security incidents, shows that the incidence of posturing and violence linked to water access has increased in recent years. Water may be associated with conflict because water resources are paramount for survival, and the need for water spans industries, economies, and communities.

Figure 1: Thirty Years of Water-Related Conflict Triggers

Notes: Instances of “conflict onset” in this graph include posturing. Data used refer to “trigger” events.

Source: Water Conflict Chronology

As urban populations and rural water demands grow in tandem, the water scarcity problem becomes more complex and solutions more elusive. The implications for wider security should not be understated.

Of the 23 countries identified by the UN as “critically” water insecure, the overwhelming majority are also categorized as “least developed countries” (LDCs) (Figure 2). The implications of this combination of deprivation and water risk are felt beyond their tragic impacts on health, sanitation, and livelihoods. They also contribute to political and economic instability in some of the most vulnerable regions.

Figure 2: Critically Water-Stressed States, by LDC Status and State Fragility Scores

Notes: The Fragile States Index scores countries from least to most fragile in the following order: sustainable, stable, warning, and alert. It does not supply a category or score to the Federated States of Micronesia, Saint Kitts and Nevis, or Vanuatu. The LDC designations reflect the list as accessed on October 30, 2023.

Source: United Nations University-Institute for Water, Environment and Health, Global Water Security 2023 Assessment

In turn, insecurity makes addressing some of the very causes of instability more costly and the means of doing so less accessible. This situation offers a potentially significant role for development banks to play.

Development Banks and Water Scarcity

Development banks are designed to better tolerate the higher levels of risk associated with development than are commercial or public and regional banks. This is core to their mission, as they are designed to lend in areas where traditional banks are reluctant to provide capital. They are able to do this with the financial support of their shareholders, who are often one or more national governments committed to supporting development initiatives.

Moreover, some development banks take on the role of a “lender of last resort” for sovereign debtors who find themselves in a precarious financial position. Positioned in this way, development banks can ensure that their loan portfolio has the desired impact and allows them to recycle their cashflow into future projects without resorting to raising capital due to poor lending results. Further, in most cases, lending does not occur on concessional terms. This means that, in most cases, a higher interest rate is charged to compensate for the risks assumed. However, restructuring of debt for the most highly indebted poor countries is becoming more prevalent.

Development banks also prioritize tackling the sustainable development goals and tend to have stronger lending guidelines in place. Through these guidelines, regulations, and conditions, financiers influence which activities are financed and which steps must be taken to ensure that the relevant stakeholders are sufficiently represented in the project implementation process. These characteristics may make development banks well-suited to address the problem of water insecurity and to prevent negative consequences from scarcity.

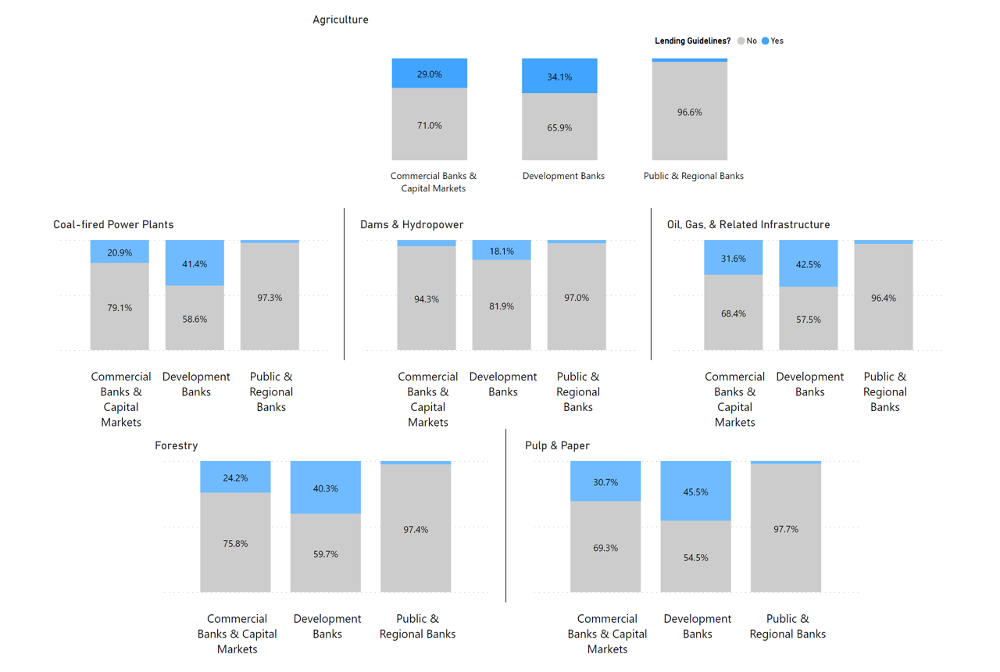

While no bank currently addresses all the water-related issues that ISS ESG Corporate Rating considers relevant to responsible lending, development banks do outperform their counterparts in other financial industries. In aggregate, development banks are more likely to have rules and regulations in place to prevent and, where necessary, minimize harm to local populations and the environment resulting from degraded or reduced water supply or poor water management.

Figure 3 maps the prevalence of lending guidelines governing some of the most water-intensive industries across Commercial Banks and Capital Markets, Development Banks, and Public and Regional Banks. According to UN Water statistics, about 69 percent of water withdrawal is used by the agricultural sector. Agriculture and other industries responsible for high volumes of freshwater withdrawal, such as energy generation and arboreal industries, depend on external financing to meet their extensive working capital needs. Development banks’ lending guidelines tend to be better specified to address challenges faced by water-intensive industries than other types of banks.

Figure 3 shows that development banks consistently have a higher prevalence of guidelines encouraging the responsible use and management of water resources than other types of banks.

Figure 3: Prevalence of Lending Guidelines to Encourage Responsible Water Use and Management in High-Withdrawal Sectors, across Three Banking Industries (%)

Notes: Banks that do not finance certain activities are not represented in the chart for that industry.

Source: ISS ESG Corporate Rating

However, as Figure 4 shows, even for agriculture, the most water-intensive industry, less than half of the opportunities that ISS ESG identifies as appropriate to promote sound water management through lending guidelines are exploited by development banks.

Figure 4: Opportunities for Development Banks to Promote Sound Water Management through Lending Guidelines in Agricultural Financing

Note: Numbers represent opportunities to promote water management, across 43 development bank ratings.

Source: ISS ESG Corporate Rating

While presently no lending industry has sufficiently robust guidelines in place to ensure that their funding does not contribute to water insecurity-related problems, guidelines to promote sound water use and management are more prevalent, by a sizable margin, among development banks than among other financial institutions.

Development banks are also equipped to cope with the risks associated with lending to the most economically and politically vulnerable states and communities, many of which are also the most water stressed. Some development banks even raise funding by issuing bonds specifically for water-related projects on the capital markets. Having lending guidelines in place for water-related projects ensures that there is a shared understanding between the bank and the borrower about how water should be treated and managed. Deviation from these may trigger constructive engagement with borrowers on how to adjust operations in order to become compliant with the guidelines.

Resources for Investors

Investors attentive to water security issues may be interested in ensuring that investees have appropriate mechanisms and guidelines to promote sustainable and responsible water use. The ISS ESG Corporate Rating provides investors with a granular breakdown of the guidelines for water use and management at each of the financial institutions in its universe of companies, as well as the existence of mechanisms to monitor impact and compliance, which can be used to inform investment decisions and identify areas for engagement.

Explore ISS ESG solutions mentioned in this report:

- Identify ESG risks and seize investment opportunities with the ISS ESG Corporate Rating.

By: Emily Helms, Senior Associate, Financials, ISS ESG