Industrialized countries around the world appear locked in a competition for finite mineral supplies critical to the energy transition. Countries and companies aim to reduce supply chain risk, yet this creates another kind of risk as offtake agreements and equity stakes claim critical mineral supplies for some while leaving other parties with insufficient supply to achieve their Net Zero ambitions.

Decarbonization and the voyage to Net Zero require many changes to the energy sector, including the electrification of transport and buildings. As we have discussed before, demand for critical minerals needed for this transition, such as cobalt, lithium, copper, nickel, rare earths (REEs), and graphite, is expected to rise substantially. Rising prices and competition help drive the IEA’s World Energy Outlook prediction that the critical minerals’ market will grow from $40 billion in 2020 to $280 billion by 2030 and $400 billion by 2050.

Offtake Agreements

Nations, companies, and investors have made critical mineral security a top priority. To supply battery production, companies have entered into agreements and taken equity stakes in supply (for example, Tesla’s involvement in a US lithium deposit). Governments are also securing stakes in the critical minerals sector. As we discussed previously, critical minerals, such as copper, lithium, cobalt, and nickel are facing substantial supply issues, from labor concerns for the cobalt supply-chain to water supply issues for copper. Therefore, supply security has become more important than price as the market tightens.

Mining companies face a variety of risks when starting operations. Offtake agreements can minimize these risks. Offtake agreements are mutually beneficial contracts between a producer and a buyer regarding future production, which add transaction certainty.

In the mining industry, offtake agreements are usually negotiated after a feasibility study is complete but before construction starts. For the producers, these agreements ensure future demand for the product, help secure financing, and provide cooperation opportunities among participants, including on ESG issues. For the buyers, offtake agreements secure future supply and can protect them from future price increases. Offtake agreements for critical minerals are becoming more common, longer-term, and larger in volume, as demand for critical minerals increases and the urgency for future supply visibility grows for the likes of battery and EV manufacturers.

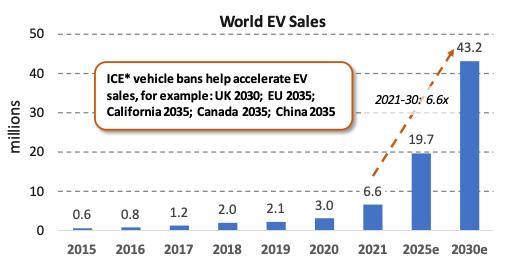

Electrification of the transport system and renewables expansion drive future critical minerals demand. Figure 1 shows the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) forecast of new electric vehicle (EV) sales through 2030, with sales growing by a factor of 6.6x from 2021 to 2030. This makes automakers and original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), including battery manufacturers, some of the most important “players” in the critical metals business. The automotive sector has been very active in trying to secure the future supply of critical minerals, and Tesla has been one of the most active companies, if not the most active one, in this respect. Tesla has multiple offtake agreements for Lithium, Cobalt, and Nickel with mining companies such as BHP, Liontown Resources, Livent, and Vale SA, among others.

Figure 1: EV Growth Over the Coming Years Is Just One of Several Demand Drivers

*ICE = internal combustion vehicles

Source: IEA, ISS ESG

The Ownership Link

Offtake buyers commonly become shareholders of the producing mining company or have stakes in the relevant mine itself. In June 2022, Stellantis, an automotive manufacturer, extended its existing offtake agreement with Vulcan Energy Resources for Vulcan’s lithium, and became the company’s second-largest shareholder. This method is also used by state-owned companies. Zijin Mining Group has a 39.6% stake in the Kamoa Kakula Copper mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and an offtake agreement for the mine’s future copper production.

State Involvement

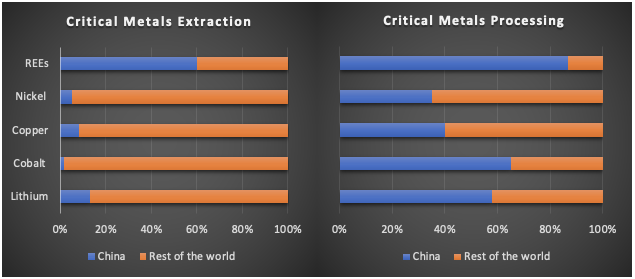

Critical minerals have become a strategic resource affecting national energy security, both for importing companies such as China and Japan, and exporting countries, such as Canada. China has already been consolidating its dominant position in the critical metals sector for some time. As Figure 2 shows, China is a major refiner and processor of the main critical minerals, while also being the dominant extractor of REEs.

Figure 2: Share of the world’s critical metals extraction and processing

Note: REEs = rare earths

Source: IEA

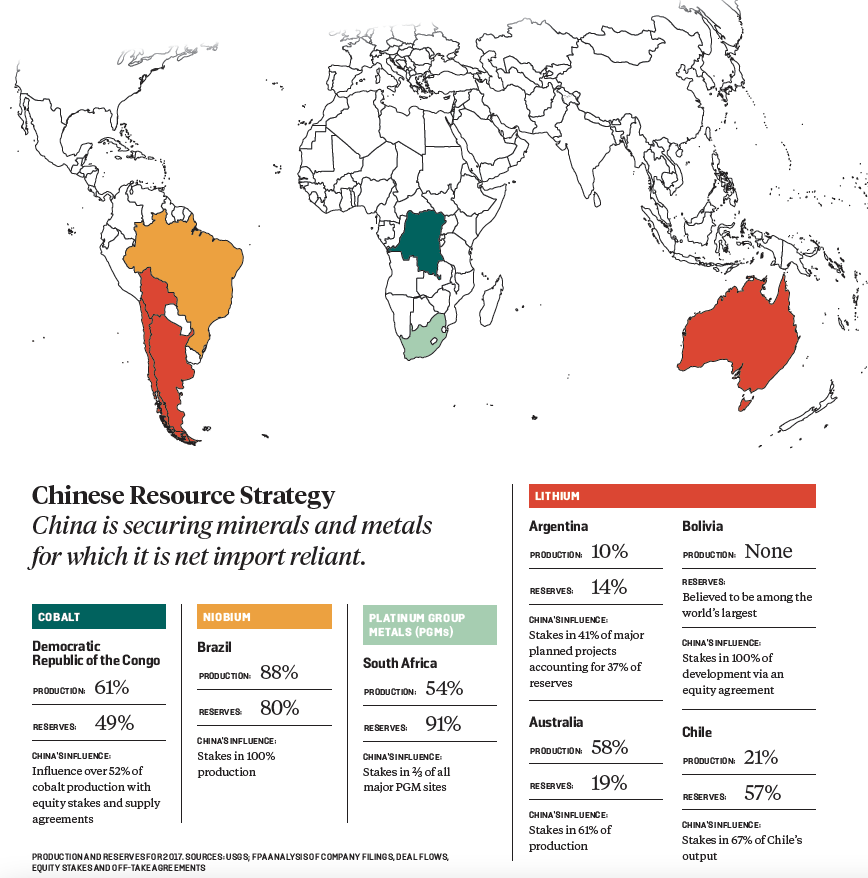

Chinese companies have been investing in overseas projects, taking stakes and making merger and acquisition deals all over the world (Figure 3). This trend has been going on for decades now, especially in the case of copper. Moreover, in the case of lithium, Chinese companies have been taking significant steps since around 2011. This trend does not seem to be stopping, as shown by the recent bid by Tianqi Lithium Corp, one of the largest lithium producers, to acquire Essential Metals Ltd., an Australian lithium explorer.

Figure 3: Chinese overseas sources of minerals and metals

Source: Foreign Policy Analytics

Moreover, state-owned companies, such as China Nonferrous Mining Corp. and Zijin Mining, have stakes in mines all over the world. Zijin has a 39.6% stake in the new Kamoa Kakula copper mine in the DRC, among others, and has recently started construction of its first lithium project, Tres Quebradas in Argentina, after acquiring Neo Lithium Corp.

The trend of resource nationalism in critical minerals is becoming more evident. For example, in 2022, Mexico (10th largest lithium reserves in the world) decided to nationalize its lithium resources. Other Latin American countries rely on state-owned mining companies for critical minerals mining, such as Codelco (copper) in Chile and Yacimientos de Litios Bolivianos (lithium) in Bolivia. Other countries retain “golden shares” in their major national resource companies, e.g., Brazil’s stake in Vale, that bestow special rights, usually veto rights and policy input.

Many African countries are also seeking to take more control over their critical minerals extraction by directly and indirectly taking bigger stakes in mining projects. For example, the DRC government owns a 20% stake in the Kamoa Kakula copper mine, which started production in 2021.

Another emerging trend regarding critical minerals, especially in Africa, is restricting or banning raw critical mineral exports from their country of origin. In December 2022, Zimbabwe banned all raw lithium exports, forcing mining companies to process lithium in Zimababwe. Arguably, this also discourages artisanal mining and shifts the processing margin to Zimbabwe.

Western countries, such as the US and Canada, are also securing their critical minerals supply and onshoring their raw material supply chains. In October 2022, Canada set a new policy limiting investments from foreign state-owned companies in the Canadian critical minerals sector. Subsequently, in November, it ordered three Chinese companies to divest from some of the Canada-based critical metals miners. In 2021, Canada and the EU agreed on a Strategic Partnership on Raw Materials, with the main focus on critical minerals and battery value chains. The US is trying to reduce its dependency on China for critical minerals by updating regulations, fostering a domestic supply chain, and investing in innovative projects, such as the new Department of Energy (DOE) project, which recovers REE and other critical minerals from fossil fuel and mining waste.

Lockout Risk

The rush for critical metals could leave some without. The increase in offtake agreements with more direct OEM involvement through stake acquisition in projects and potential vertical integration of major companies, such as Tesla, is reducing supply risk. This trend could also increase market power for these corporations, though, as competitors (both national or corporate) are locked out.

The trend raises concerns about the global availability of critical minerals and the potential need for more new mining projects. To achieve Net Zero, the IEA forecasts that 50 new lithium, 60 nickel, and 17 cobalt projects are required by 2030. The significant timing risk surrounding these new projects (or in some cases the uncertainty about whether the projects are permitted to proceed at all) highlights the risk to countries and manufacturers who do not lock in supply agreements and equity stakes now.

The ESG Positive Side

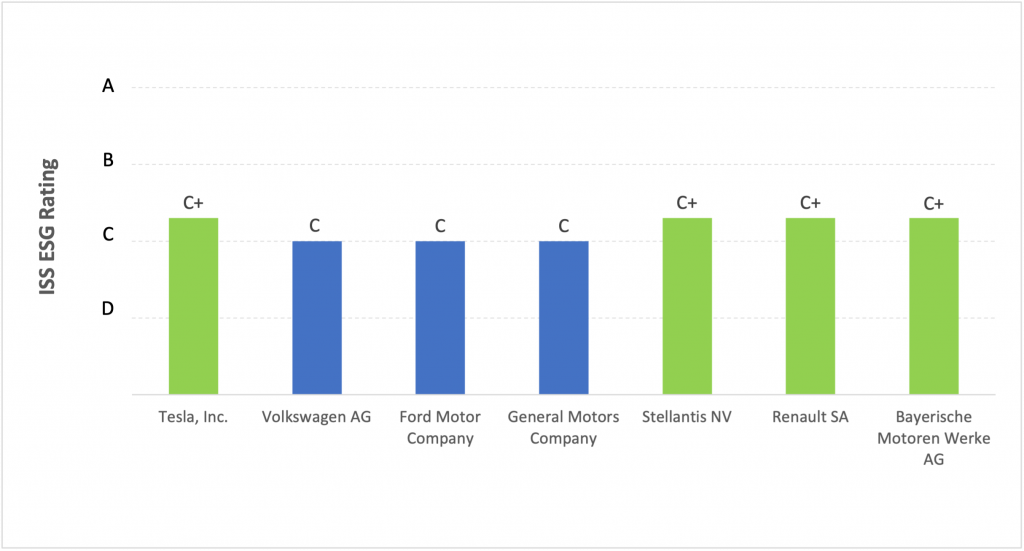

Offtake agreements and equity stakes for supply security can also be used to foster better behavior along the supply chain. Companies are being pressured by evolving regulation from around the world to perform better on ESG-related issues, such as decarbonization, human rights, and supply chain transparency. In turn, offtake agreements can provide a platform for adhering to those regulations, by raising supply chain transparency, targeting sustainable buyers and products, and fostering collaboration. Some agreements already contain signs of ESG considerations on the part of both customers and suppliers. Automakers are at the forefront of ESG performance and commitment, as can be seen from Figure 4, with the companies considered “Prime” being colored green.

Figure 4: ISS ESG ratings of the automakers heavily involved in offtake agreements

Source: ISS ESG

Sustainability Collaboration

BHP and Tesla are an example of how offtake agreements can encourage sustainability. BHP and Tesla’s offtake agreement supports both parties’ efforts to increase sustainability in the battery supply chain. Vale SA is targeting the EV industry specifically for offtake agreements. Mining companies using new low-carbon lithium extraction methods, such as direct lithium extraction (DLE), which uses geothermal energy for lithium extraction, are being targeted for offtake agreements. One such company, Vulcan Energy Resources, has offtake agreements with Renault, Stellantis, and Volkswagen. Renault’s partnership with Vulcan is expected to reduce between 300 to 700 kg of the CO2e emitted to build a 50-kWh battery.

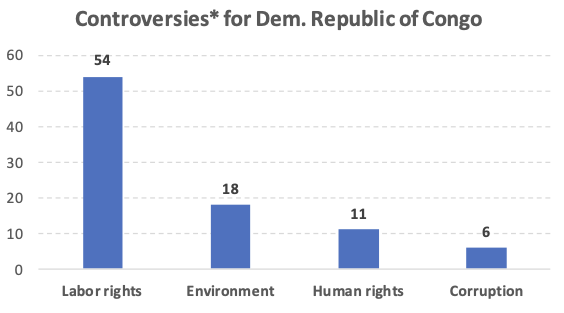

Glencore recently entered multiple cobalt offtake agreements from their DRC mining operations, the DRC currently being the world’s leading cobalt supplier. In many cases, these included agreements on yearly independent auditing of their operations against the “Cobalt Refiner Supply Chain Due Diligence Standard” of the Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI). Buyers are not just securing future supply, they are also trying to avoid the negative risks and impacts associated with cobalt production in the DRC, e.g., labor rights violations, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: ISS ESG Research Reveals Considerable DRC Labor Rights Controversies

*ISS ESG Norm-Based Research assesses companies’ adherence to international norms on human rights, labor standards, environmental protection, and anti-corruption set out in the UN Global Compact and OECD Guidelines.

Source: ISS ESG Norm-Based Research

Competition for critical minerals among governments can lead to innovation. The current US push for a transparent, secure, and domestic supply of critical minerals is encouraging innovative solutions and new technologies. In addition to the innovative REE minerals extraction method used in the new DOE project, US efforts to secure critical minerals domestically encourage projects such as the Hell’s Kitchen Lithium and Power project in California of Controlled Thermal Resources. The project is a direct lithium extraction initiative.

The Race

The critical minerals market can seem like a land rush to secure supplies. A clear competition for finite critical minerals is ongoing: there are preoperational mines with nearly all production pre-sold. Around 90% of Liontown Resources’ Kathleen Valley Project’s spodumene concentrate (lithium) is reserved by offtake agreements with Ford, Tesla, and LG Energy Solutions. All of the new Kamoa Kakula mine’s Phase 1 copper production is under offtake agreements with China’s state-owned Zijin Mining and Citic Metal. Resource nationalization seems to be trending in Latin America, with Africa not far behind. Western countries, such as Canada and the US, are strengthening their own positions and narrowing the gap with China. Governments and companies who stay on the sidelines may be left with few options.

This market presents investors with opportunities but also with the challenge of identifying ESG-compatible investments. ISS ESG products such as the ESG Country Rating and ESG Corporate Rating and Norm-Based Research can support ESG investors as they pursue opportunities in the critical minerals market.

Explore ISS ESG solutions mentioned in this report:

- Identify ESG risks and seize investment opportunities with the ISS ESG Corporate Rating.

- Assess companies’ adherence to international norms on human rights, labor standards, environmental protection and anti-corruption using ISS ESG Norm-Based Research.

- Access to global data on country-level ESG performance is a key element both in the management of fixed income portfolios and in understanding risks for equity investors with exposure to emerging markets. Extend your ESG intelligence using the ISS ESG Country Rating and ISS ESG Country Controversy Assessments.

By: Nicolaj Sebrell, CFA, Head of Energy, Materials, & Utilities, ISS ESG

Filip Veintimilla Ivanov, Analyst, Metals & Mining, ISS ESG